By Fred Mazelis in the USA:

The bicentenary of Frederick Douglass

A leading figure of the anti-slavery struggle

20 December 2018

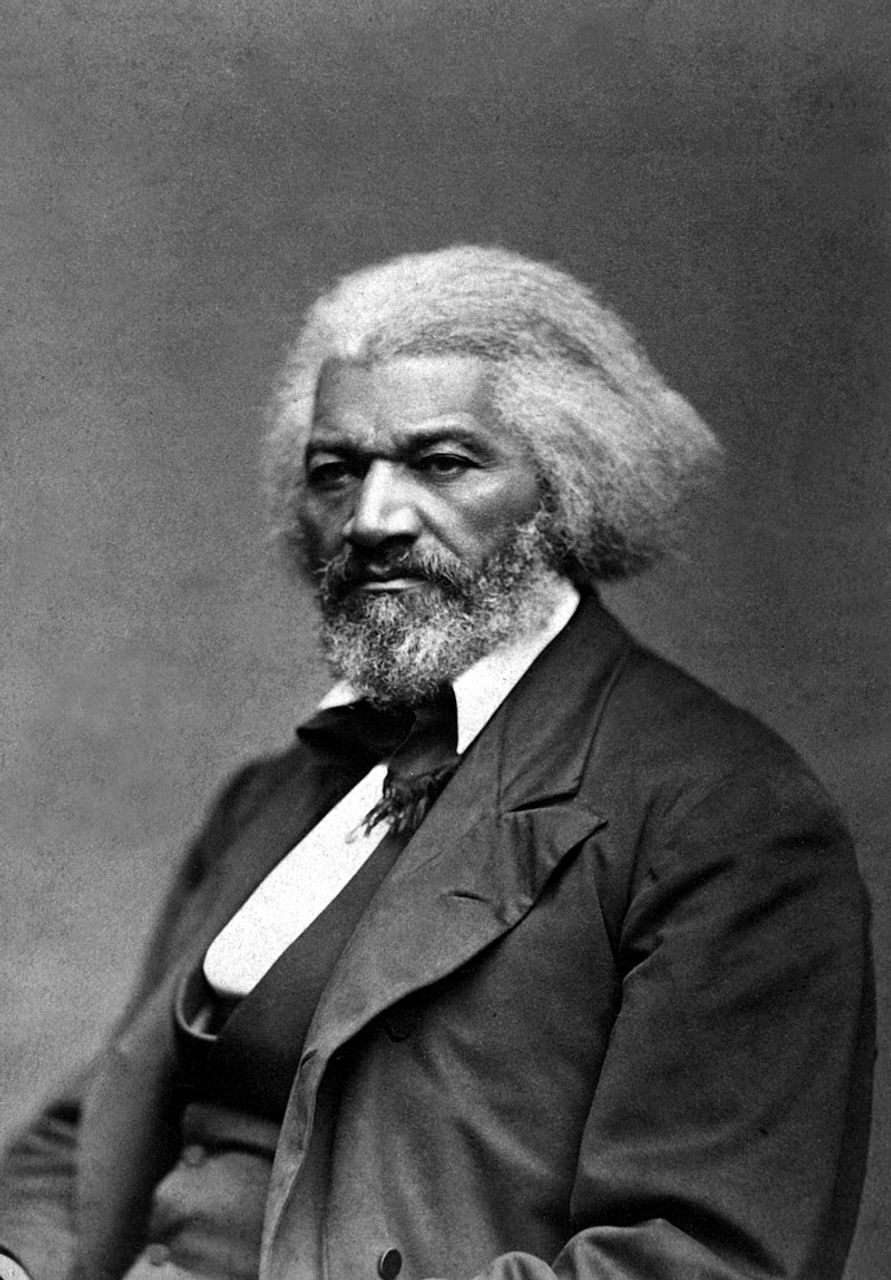

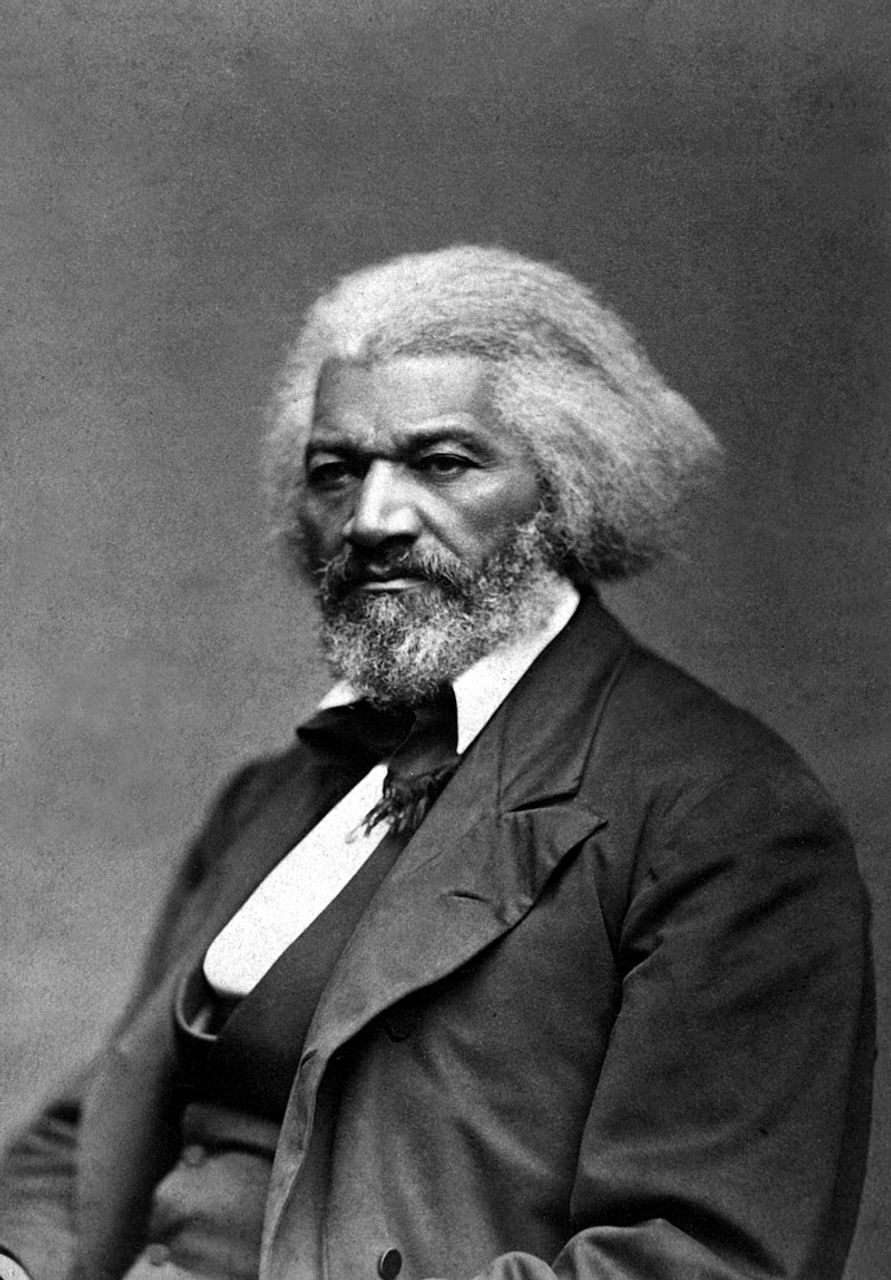

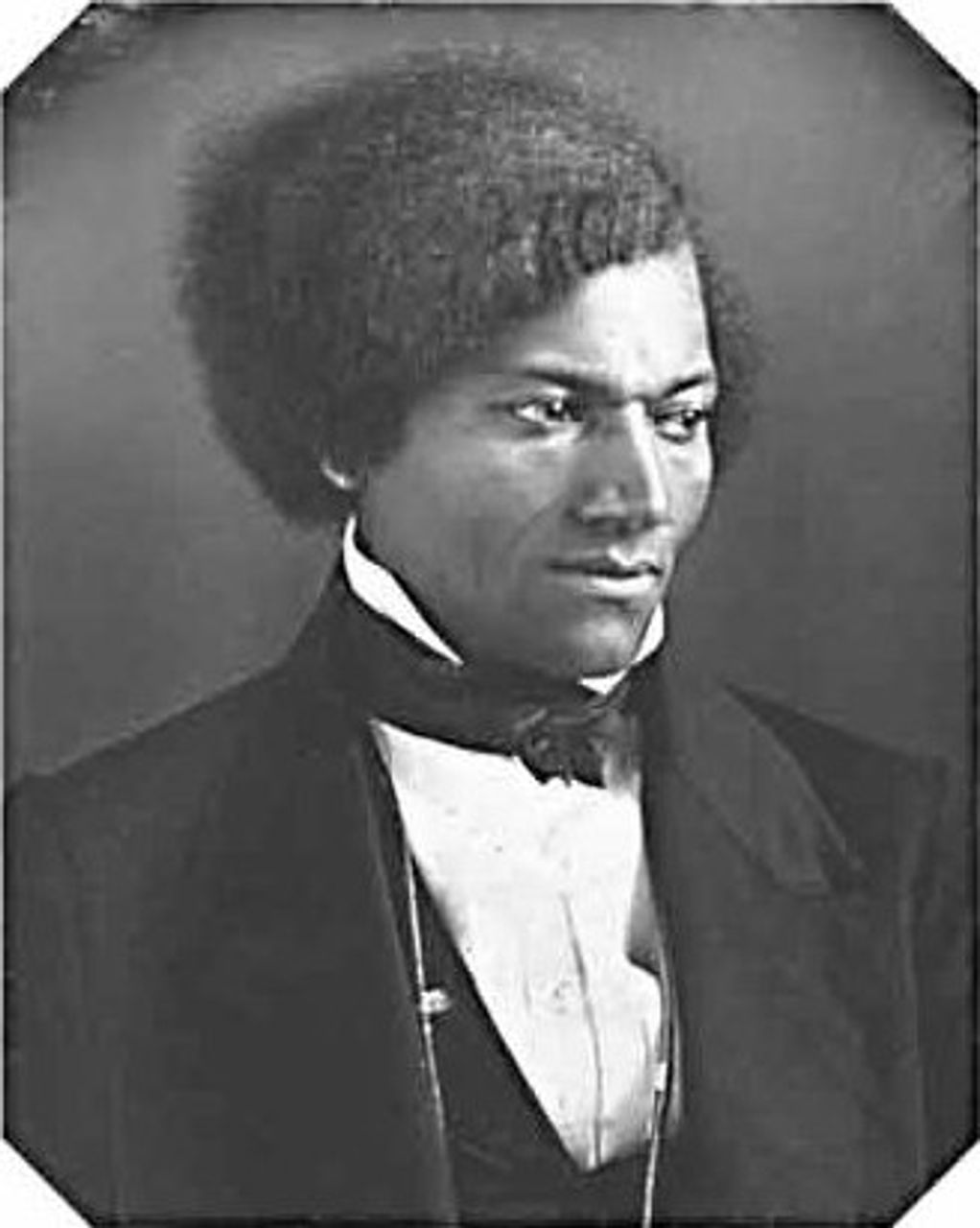

This year marked the bicentenary of Frederick Douglass (1818-1895), one of the greatest figures of 19th century America, whose oratory, writings and agitation helped mightily to inspire the abolition of slavery in the Civil War, the Second American Revolution.

Born into slavery on Maryland’s Eastern Shore, the mixed-race Frederick Bailey barely knew his mother, and was separated from his grandmother at the age of six. He never knew the identity of his father, but later wrote that it was “whispered [that it was] my master.”

Showing both intellectual curiosity and determination at an early age, the young man began learning the alphabet from the wife of his master’s brother, with whom he was then living in Baltimore. Life in a major city gave him certain opportunities for self-education, extremely limited though they were. Frederick was able to play in the streets with other boys. When the head of the household cracked down on the teaching, he studied surreptitiously, especially about the meaning of slavery. Within a few decades, the young slave became one of the greatest autodidacts in American history.

Frederick fought back successfully at the age of 16 against a brutal overseer. After several failed attempts, he escaped to freedom in 1838 at the age of 20, later changing his name to Frederick Douglass (the surname suggested by a friend who took it from a character in Sir Walter Scott’s The Lady of the Lake). He was soon joined by Anna Murray, who had helped him prepare his journey north. They married in New York City and settled in New Bedford, moving later to Lynn, Massachusetts.

As early as 1839 Douglass was speaking at church meetings, relating the story of his escape from slavery and speaking on the struggle for abolition. It was a major address at a meeting of the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society on August 16, 1841, when he was only 23 years old, that brought him to the attention of leading abolitionists in the audience, including William Lloyd Garrison and Wendell Phillips. Garrison, some 13 years Douglass’s senior, had launched The Liberator in 1831, and was the acknowledged leader of the anti-slavery struggle. Douglass soon devoted himself full-time to the effort, as a lecturer and activist.

This work took him away from home for long periods of time, even as he and his wife became the parents of five children. Rosetta, Lewis, Charles and Frederick Jr. survived to adulthood. A second daughter, Annie, died at the age of 10. Anna Douglass died in 1882, after 44 years of marriage.

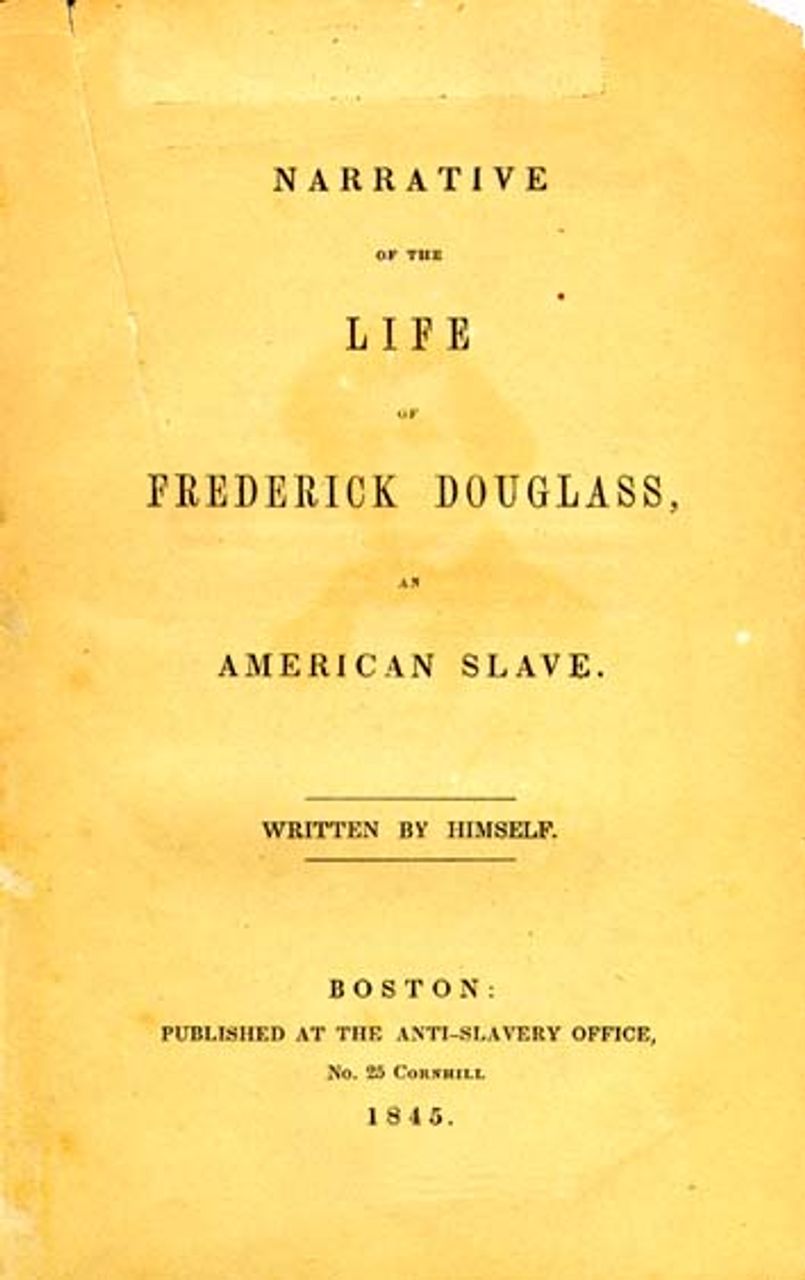

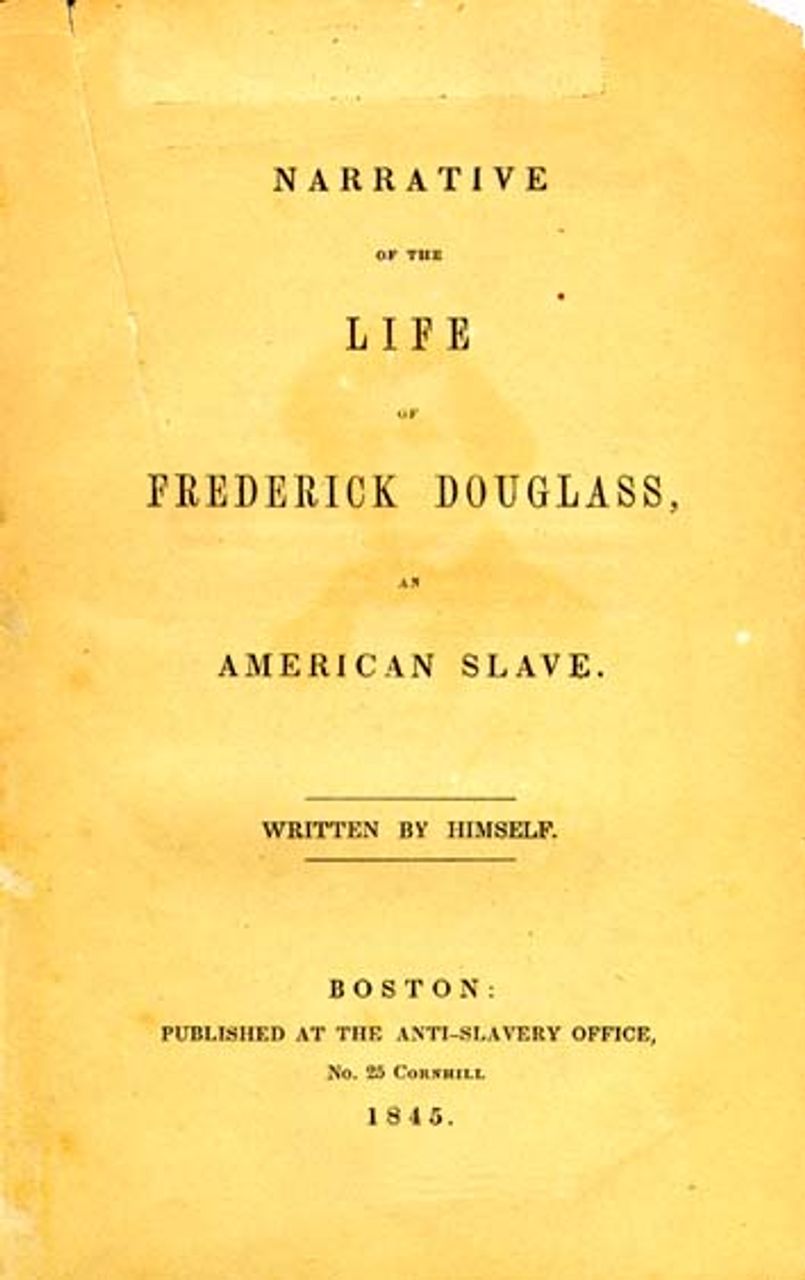

The first of three autobiographies, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, was published in 1845, and quickly reached tens of thousands of readers. Douglass went on to write two other autobiographies, including My Bondage and My Freedom, in 1855, and Life and Times of Frederick Douglass, in 1881, which he revised and updated in 1892. For most of his life Douglass was also the publisher of newspapers espousing his views. Douglass’s biographers include William McFeely, in 1991, and David Blight, whose impressive and exhaustive account has appeared in this bicentenary year.

Writing and speaking long before the advent of modern communications technology, Douglass nevertheless became known to millions through the enormous power of his oratory and his message of intransigent and revolutionary opposition to slavery. The strength of the speeches was wedded to their content, to the passionate struggle for freedom against slavery and racial oppression.

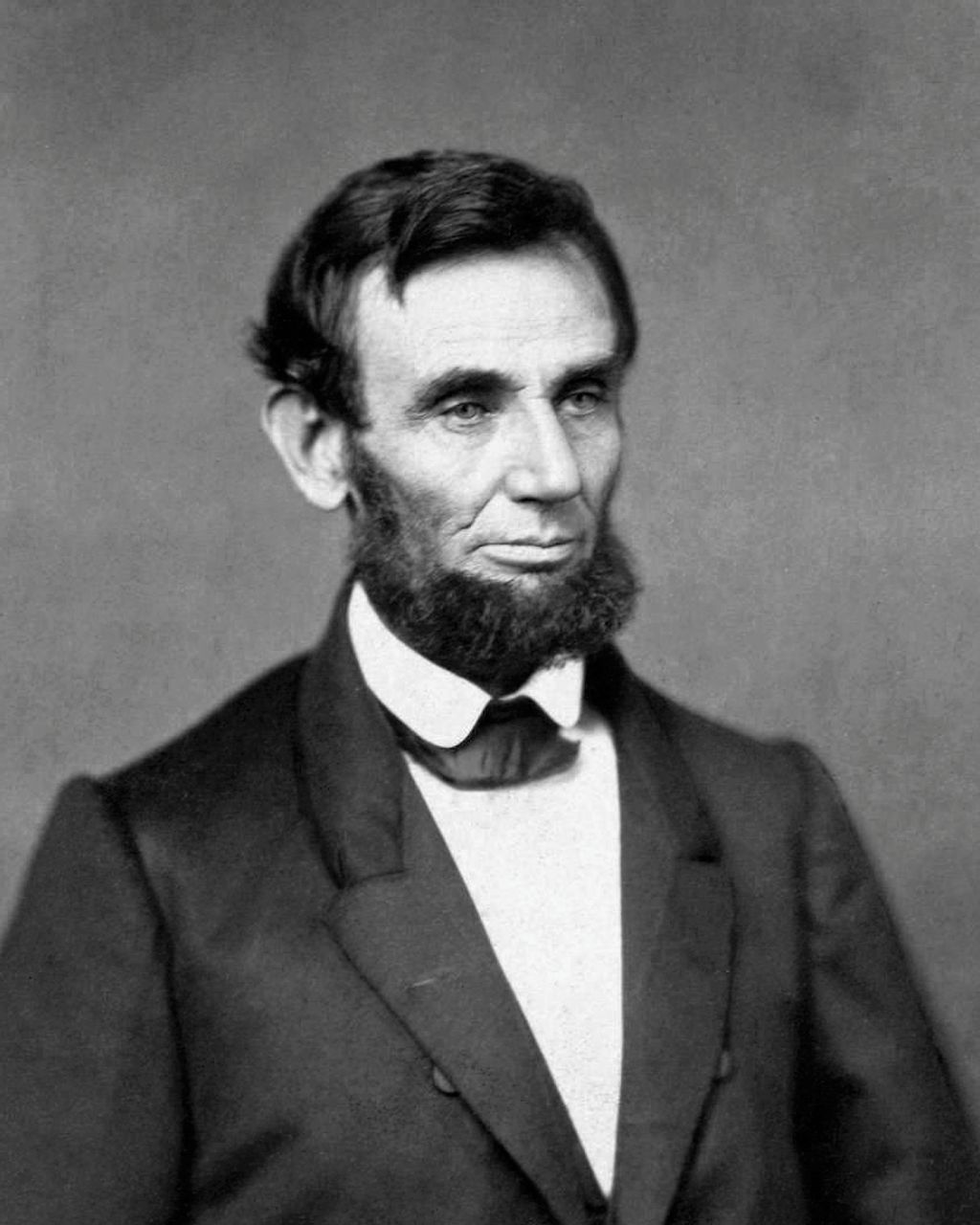

In the course of his long life, Douglass knew or collaborated with all of the major anti-slavery and other radical figures of the period, including, in addition to Garrison and Phillips, Harriet Beecher Stowe, Harriet Tubman, Ida B. Wells, women’s suffrage leaders Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, and many others, including Mark Twain. Douglass met eight US presidents, serving in the administrations of several of them in his later years. His relationship with the first of these, Abraham Lincoln, whom he met with twice in the course of the Civil War, was by far the most significant.

A lengthy trip to Ireland and England between 1845 and 1847 played a key role in Douglass’s growth as an Abolitionist leader. He spent part of the time with Garrison in London. Douglass, developing a broader international outlook, identified with the Irish struggle for independence and marveled, in a letter home, at the difference with which he was treated: “No insults to encounter—no prejudice to encounter, but all is smooth—I am treated as a man and equal brother.” It was also during this trip that British sympathizers joined to buy the escaped slave’s freedom from his Maryland master, so that Douglass need not fear capture when he returned to the struggle in America.

Back in the US, Douglass settled in Rochester, New York, where he would live for the next 25 years. He soon launched his North Star, the first of the newspapers that he led, which was known for its uncompromising opposition to schemes for colonization in Africa as a means of ending slavery.

In the wake of the Mexican War—which Douglass had bitterly opposed, correctly characterizing it as a means of extending the slave system—the storm clouds that were to erupt in civil war continued to accumulate. This was a period in which Douglass more than once faced physical peril from pro-slavery elements in the North.

As he came into his own as a leading abolitionist, and moreover the most famous black abolitionist, Douglass was increasingly willing to do battle with old allies on issues of strategy and tactics. This led to a sharp and lengthy dispute with his mentor and teacher William Lloyd Garrison.

A major point of dispute between Garrison and Douglass was the attitude to be taken toward the US Constitution. Garrison regarded it as a purely pro-slavery document, while Douglass came to recognize its connection to the revolutionary ideals of the Enlightenment, and the necessity for anti-slavery advocates to make use of the Constitution and argue for the extension of its promises and guarantees to Americans of African ancestry.

… A stirring example of Douglass’s outlook can be found in his famous speech given to the Rochester Ladies’ Anti-Slavery Society on the day after Independence Day in 1852. “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?” came to be known as The Fifth of July Speech. It is both an indictment of slavery and the compromise with it in the Constitution, and at the same time a ringing defense of that Constitution and of the revolutionary struggle that gave rise to it and that inspired innumerable struggles against absolutism and despotism around the world.

Douglass’s tribute to the American Founding Fathers in this speech is a particularly eloquent passage and at the same time a devastating indictment of the political spokesmen of American capitalism today. “They were peace men; but they preferred revolution to peaceful submission to bondage. They were quiet men; but they did not shrink from agitating against oppression. They showed forbearance; but that they knew its limits. They believed in order; but not in the order of tyranny. With them, nothing was ‘settled’ that was not right. With them, justice, liberty and humanity were ‘final’; not slavery and oppression. You may well cherish the memory of such men. They were great in their day and generation. Their solid manhood stands out the more as we contrast it with these degenerate times.”

The breach between Garrison and Douglass was not fully healed until 1873. When the older man died in 1879, Douglass eulogized him as follows at a memorial service in Washington DC: “It was the glory of this man that he could stand alone with the truth, and calmly await the result.”

Douglass was among the few abolitionists who gave his full support to the struggle for women’s rights. He attended the Seneca Falls, New York women’s rights convention in 1848, but 21 years later, in the wake of the Civil War, Douglass and Susan B. Anthony parted ways when she refused to support the 15th Amendment, enacted on Feb. 3, 1870.

She opposed extending the right to vote to the former slaves as long as women were still denied access to the ballot. As William McFeely points out, Anthony, “who had been steadfast in her opposition to slavery, crossed the line into racism when she said that women were more intelligent than the black men who, she now saw, were competing with her and her fellow women for the vote.”

The question of whether the United States would continue as half-slave and half-free was posed with growing urgency in the 1850s. This decade saw some major political gains for the advocates of slavery, beginning with the Fugitive Slave Act, part of the Compromise of 1850, which obliged the Federal government to actively assist in the return of runaway slaves to their masters. The Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854 laid the groundwork for the extension of slavery to US territories by stipulating that settlers, and not the federal authorities, would make the decision on the question. And finally, in 1857, the US Supreme Court issued its infamous Dred Scott decision, denying citizenship to all slaves or ex-slaves, and decreeing that Congress could not prohibit the extension of slavery in the territories.

Those who sought to solve the slavery question through gradual abolition or some other compromise looked on these developments with dread and pessimism. However, Douglass was not fundamentally discouraged. More intransigent than ever, he sensed that the actions of the pro-slavery forces reflected weakness, not strength. He recognized the necessity for a national political solution. While he did not welcome violence, neither did he rule it out.

This decade saw the peak of Douglass’s eloquence as a public speaker. Two dates stand out in particular—the above-cited Fifth of July Speech, and the “West India Emancipation” speech, delivered on August 3, 1857, to mark the twenty-third anniversary of the abolition of slavery in those British territories. This address, delivered only months after the Dred Scott decision, is if anything even more famous than the earlier one. Douglass’s words resonate as powerfully today as it did in the 19th century:

“If there is no struggle there is no progress,” he said. “Those who profess to favor freedom and yet deprecate agitation are men who want crops without plowing up the ground; they want rain without thunder and lightning. They want the ocean without the awful roar of its many waters.

“This struggle may be a moral one, or it may be a physical one, and it may be both moral and physical, but it must be a struggle. Power concedes nothing without a demand. It never did and it never will. Find out just what any people will quietly submit to and you have found out the exact measure of injustice and wrong which will be imposed upon them, and these will continue till they are resisted with either words or blows, or with both.”

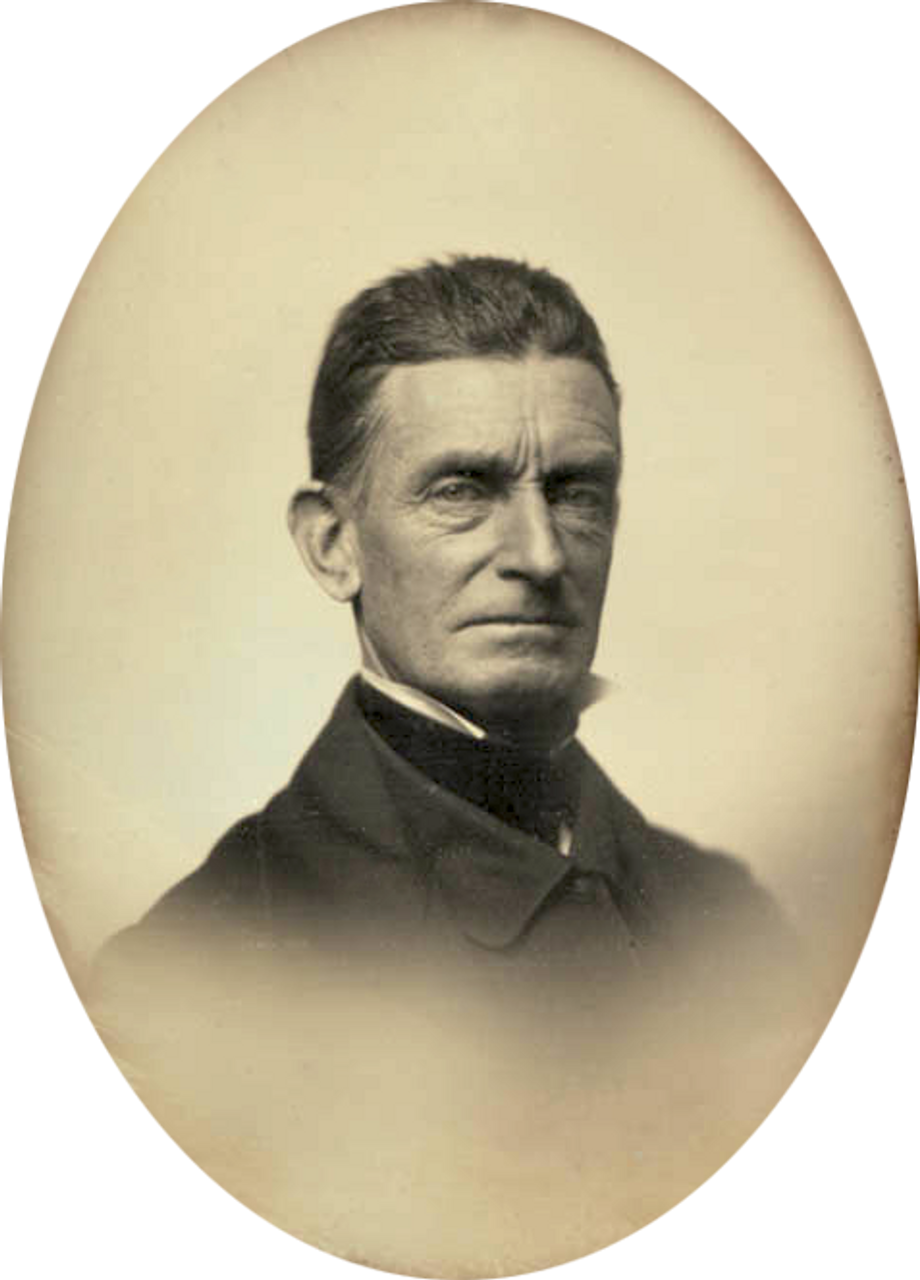

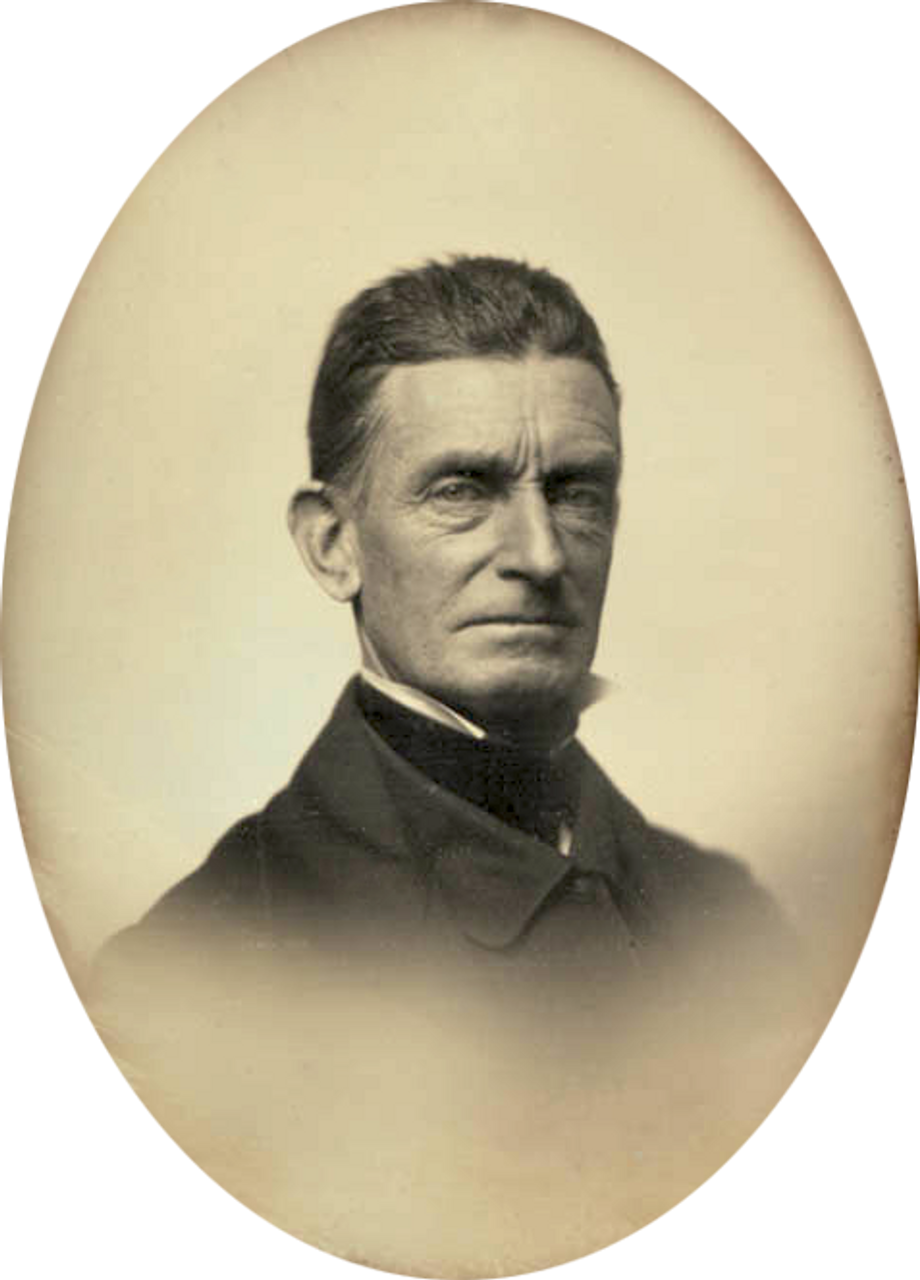

It was in this revolutionary frame of mind that Douglass met with John Brown, the fiery abolitionist who went on to lead the failed raid on the US arsenal in Harpers Ferry in October 1859. Douglass was drawn to the mesmerizing figure of Brown, but when told the details of the planned raid, he refused to participate, warning Brown that it was foolhardy and suicidal. He had met with Brown, however, and had also helped to raise funds for his activities. Facing the danger of arrest and prosecution, Douglass left for Canada days after the Harpers Ferry raid, narrowly escaping apprehension by US marshals.

He soon went on to England, on a trip that had been previously planned. By this time, through the combination of his writings and speeches as well as his trips to Europe, Douglass had already become the most prominent black man in America. He stayed in England for about four months, returning after the tragic death of his young daughter Annie, even though he still faced some risk because of his association with John Brown. While he lay low for several weeks, by August of 1860, in the words of biographer McFeely, “he discovered that for the first time in his life, he was in the political mainstream.”

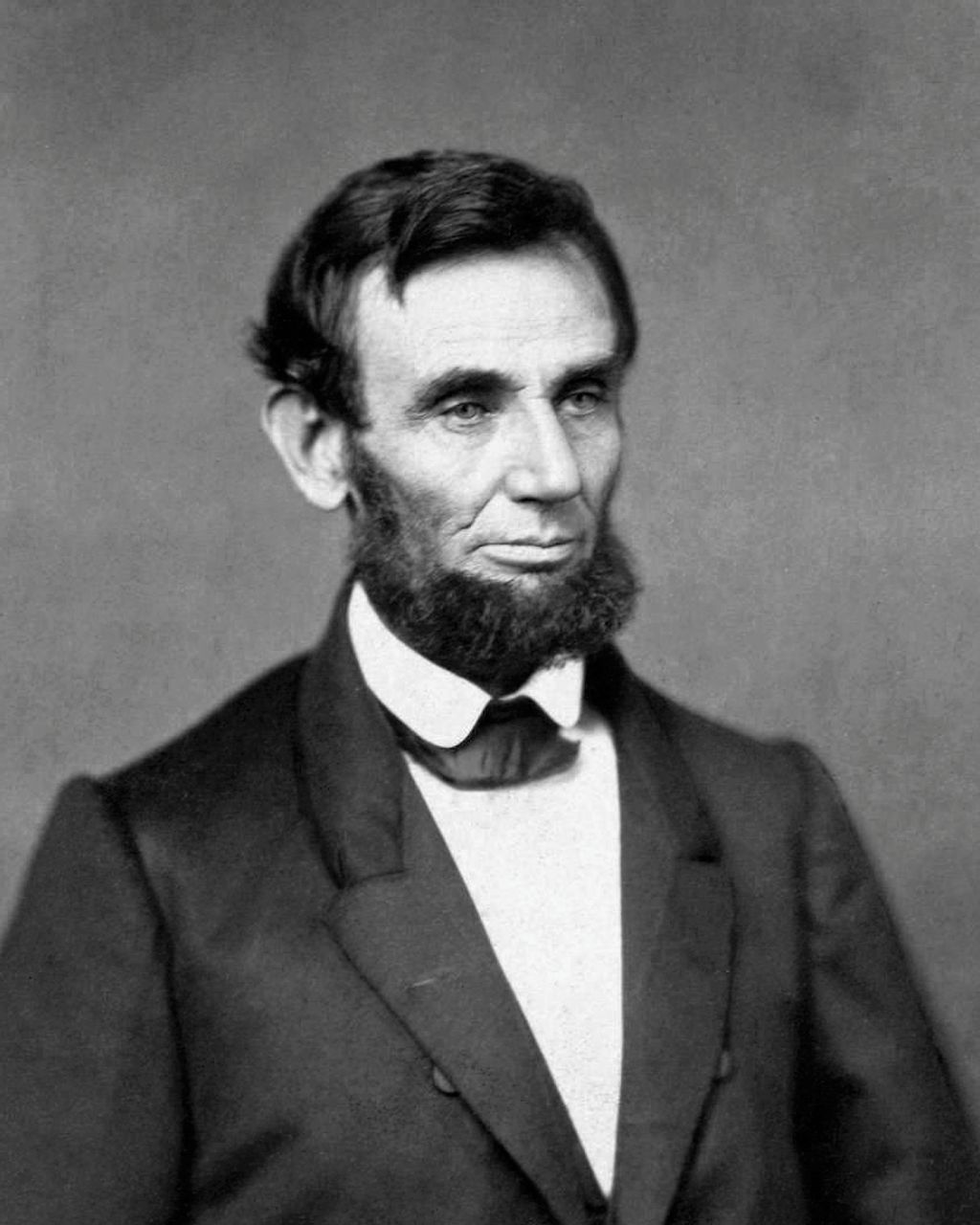

The Republican Party, formed only a few years earlier, now moved in Douglass’s direction, adopting a platform that more militantly opposed the extension of slavery. The black abolitionist disagreed with those who considered Abraham Lincoln too moderate in his views to merit critical support in the presidential election of 1860. He made the following assessment: “While I see…that the Republican party is far from an abolition party, I cannot fail to see also that [it] carries with it the antislavery sentiment of the North, and that a victory gained by it in the present canvass will be a victory gained…over the wickedly aggressive pro-slavery sentiment of the country.”

Douglass’s political appraisal was borne out in a somewhat circuitous way after Lincoln won in November. The victory that Douglass hoped for was followed not by a retreat by the pro-slavery forces, but by the formation of the Confederacy. It was this in turn that made the Civil War inevitable, and eventually the abolition of slavery. The image of John Brown became that of an abolitionist prophet, not a lunatic, as previously depicted. As quoted by David Blight from a speech early in the Civil War, Douglass declared, “Good old John Brown was a mad man at Harpers Ferry. Two years pass away, and the nation is as mad as he is.”

As Douglass became the most eloquent champion of unconditional victory over the slavocracy, Blight compares him to Walt Whitman, “but with blunter edges.” “The cry is now for war, vigorous war, war to the bitter end, and war till the traitors are effectually and permanently put down,” wrote Douglass. In words that foreshadowed the campaigns of Union military leaders Sherman and Sheridan, Douglass thundered, “Let the ports of the South be blockaded, let business there be arrested; let provisions, arms and ammunition be no longer sent there, let the grim visage of a Northern army confront them from one direction, a furious slave insurrection meet them at another, and starvation threaten them from still another.”

But Douglass also thundered against Lincoln, who for definite political reasons insisted at this stage that the war was to preserve the Union, and not to end slavery.

The president, Douglass said, “is tall and strong but he is not done growing.” He demanded an immediate change in war aims. He denounced the administration’s return of runaway slaves, and Lincoln’s rescinding of General John C. Fremont’s emancipation of slaves in the border state of Missouri.

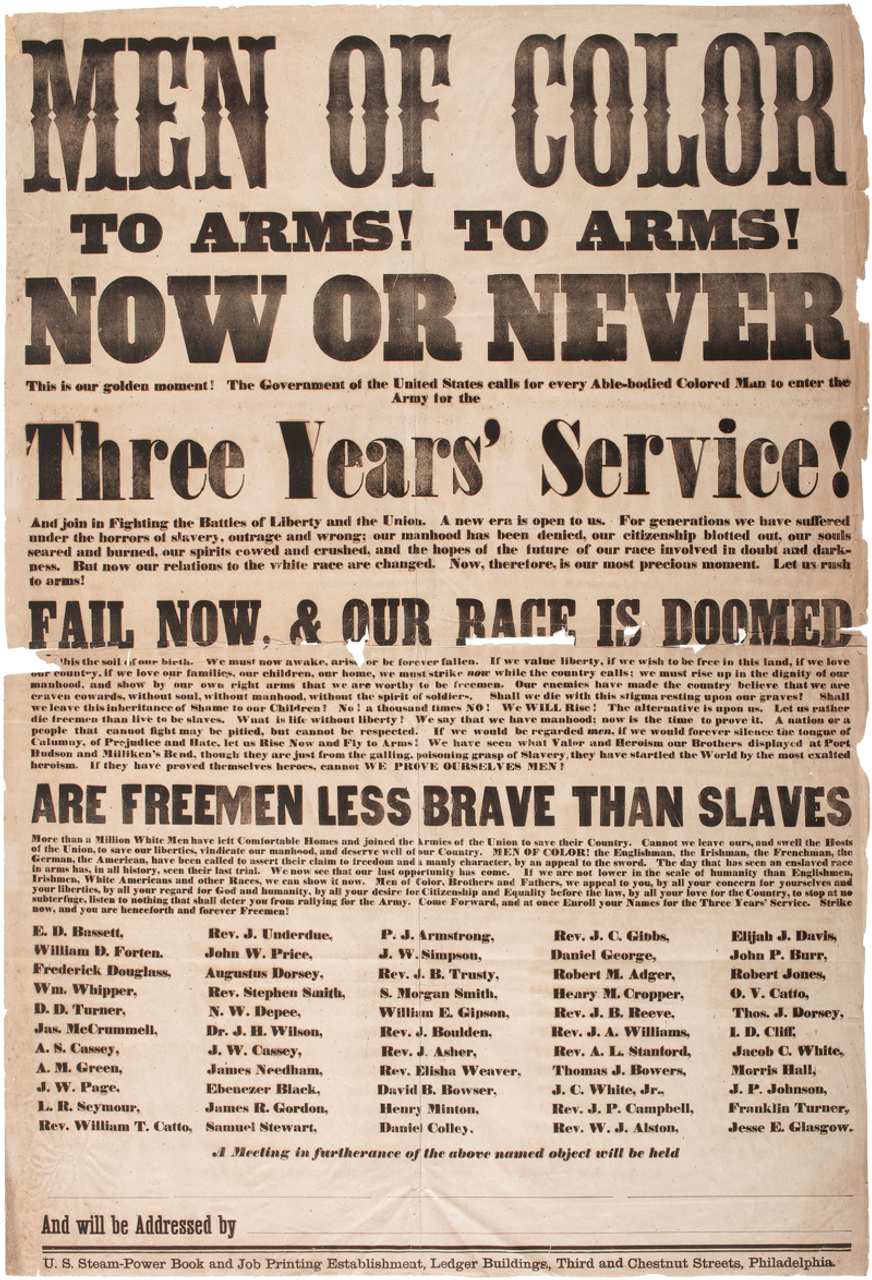

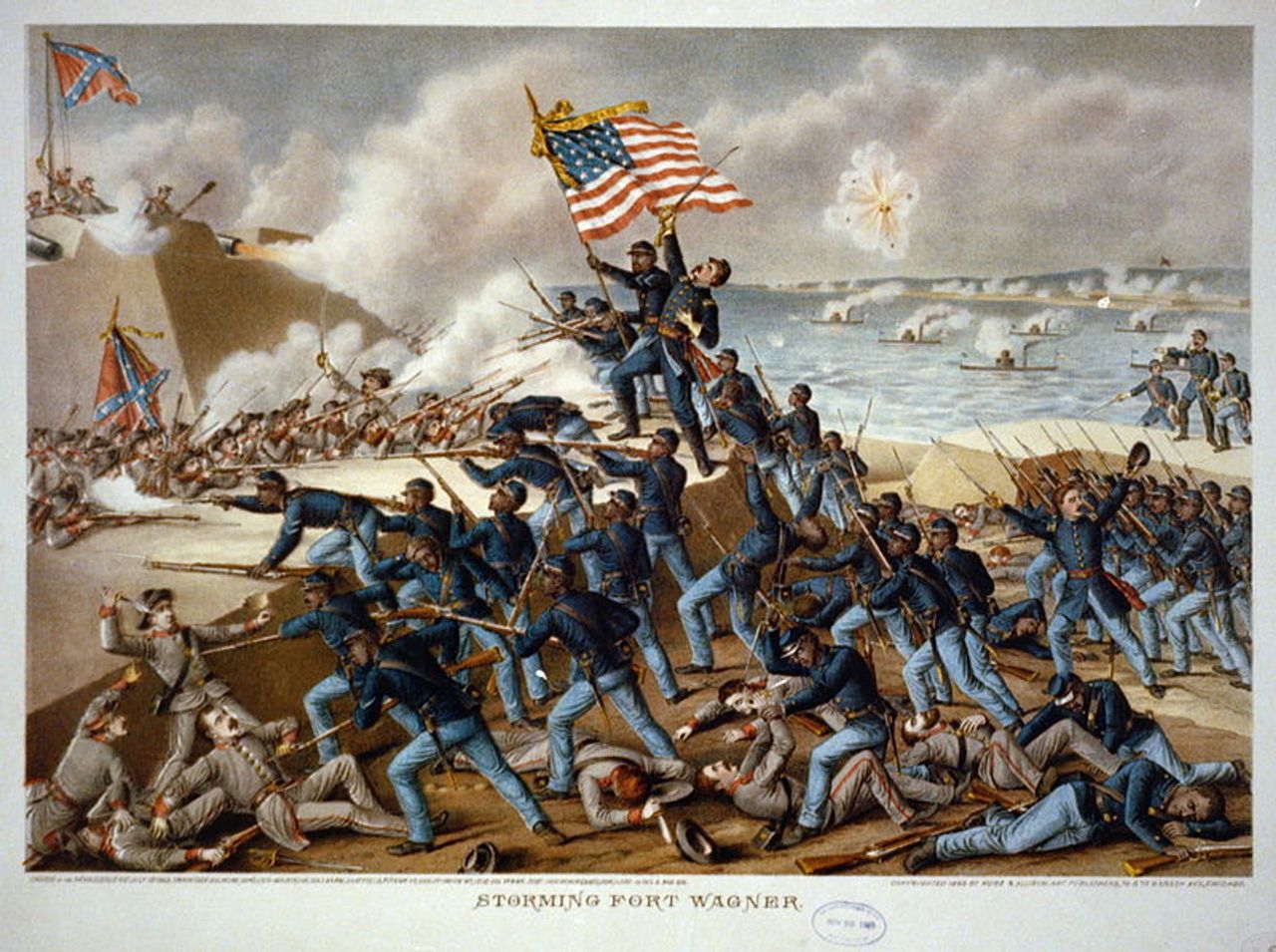

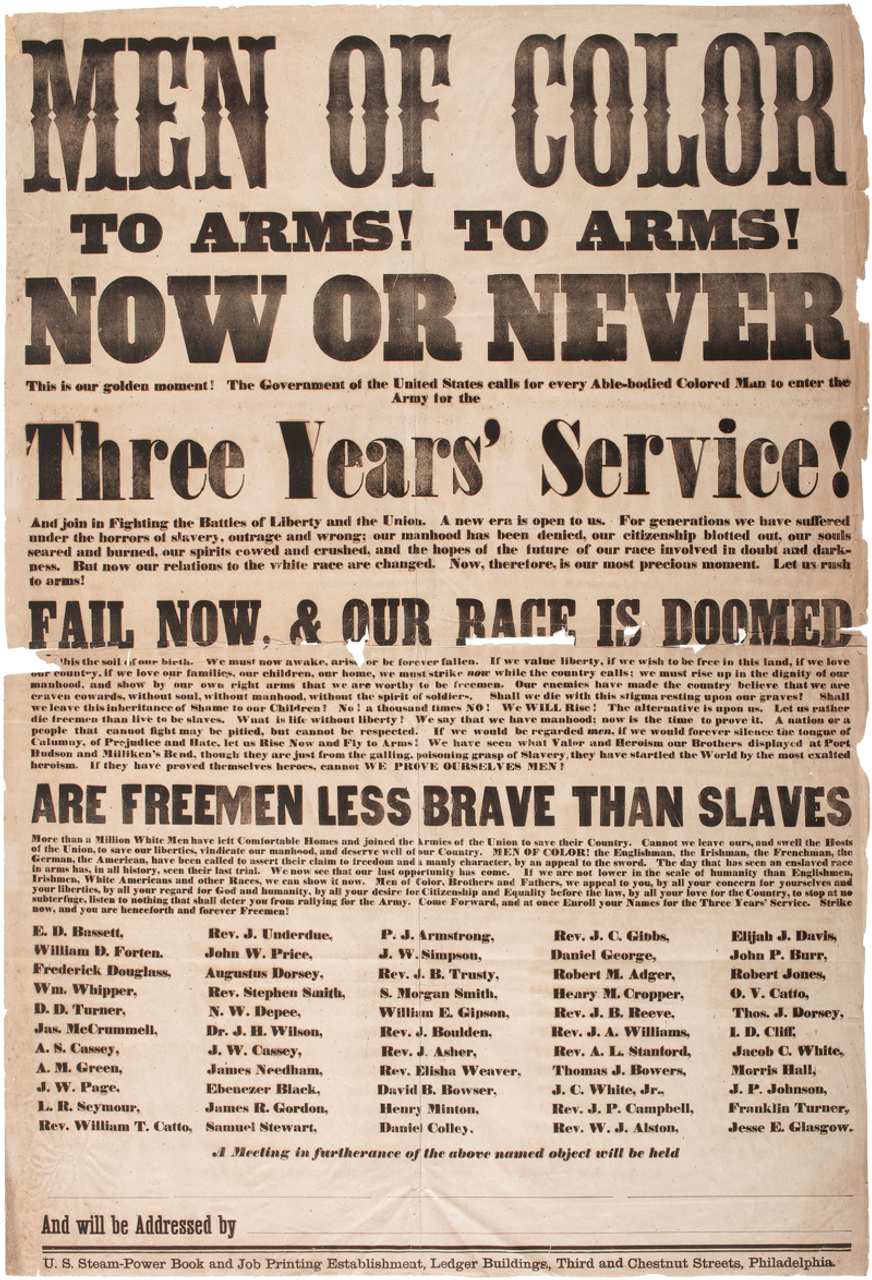

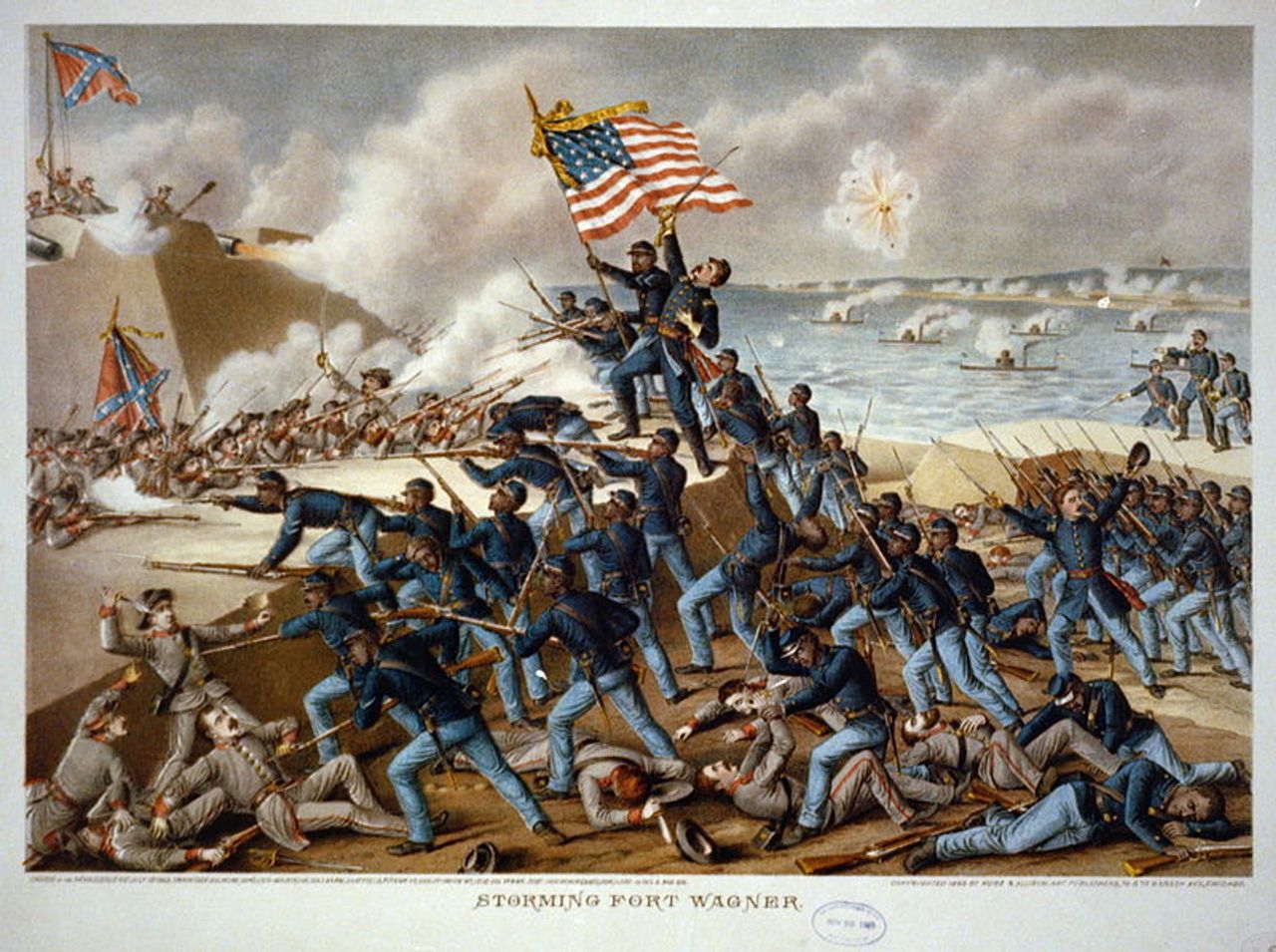

As the conflict deepened, however, the war to preserve the Union became a war to end slavery. Lincoln began to listen to the demands of Douglass and others. The Emancipation Proclamation of January 1, 1863, followed by the effort to recruit free blacks and slaves to the Union army, was a key turning point. Douglass eagerly threw himself into the drive for recruitment of black soldiers, who played a key role in the defeat of the Confederacy. Two of his sons joined the famous 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment, which drew African Americans from across the North.

Douglass met with Lincoln twice. The first occasion was in August 1863. “I went directly to the White House [and] saw for the first time the President of the United States,” he wrote. “Was received cordially and saw at glance the justice of the popular estimate of his qualities expressed in the prefix Honest to the name Abraham Lincoln.”

Douglass thanked Lincoln for the recent order answering the Confederacy’s threat to treat all captured black Union soldiers as insurrectionary slaves with the decree that “for every soldier of the United States killed in violation of the laws of war a rebel soldier shall be executed.”

Lincoln “went on to deny that he was guilty of ‘vacillation’ and implied that what Douglass was seeing was steady, if perhaps slow, progress, rather than any indecision on his part,” explains McFeely. “Douglass came away convinced that once Lincoln had taken a position favorable to the black cause, he could be counted on to hold to it.”

This was a relationship, and a role for each of these figures, that could hardly have been imagined 25 years earlier, when Douglass had just escaped to freedom and Lincoln was a young lawyer and a member of the Illinois General Assembly.

The Civil War ended but the struggle for full racial equality continued. The 13th Amendment to the Constitution, abolishing slavery, was ratified and enacted in 1865. Douglass devoted his energies to the struggle that would lead to the enactment of the 14th and the 15th Amendments, guaranteeing, respectively, equal protection under the law and extending the right to vote to African Americans. In a speech given in Baltimore on September 29, 1865 he gave voice to his great hopes in the aftermath of the victory against slavery and the “rebirth of freedom.” Addressing his audience, as McFeely explains, “with an image Langston Hughes would use in perhaps the greatest of his poems” [“The Negro Speaks of Rivers”], Douglass said that “the loftiest and best eloquence which the country has produced, whether of Anglo-Saxon or of African descent, shall flow as a river, enriching, ennobling, strengthening and purifying all who lave in its waters.”

With the assassination of Lincoln, however, Andrew Johnson, the Tennessee Democrat who had been elected as Lincoln’s Vice-Presidential running mate only months earlier, had entered the White House. Douglass was part of a black delegation that met with Johnson in 1866, a meeting that only underscored Johnson’s hostility to defending the rights of the freed slaves in the South.

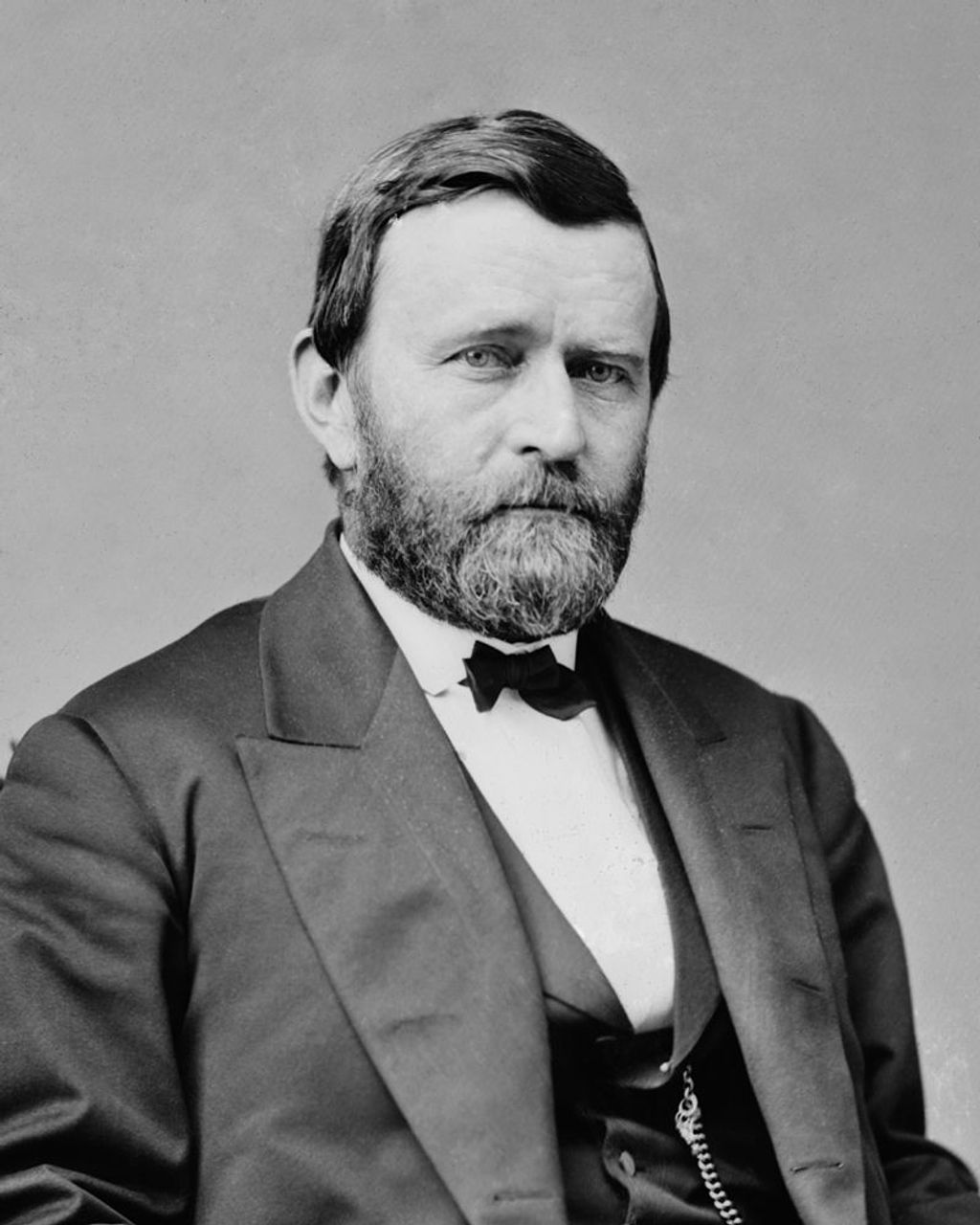

Douglass endorsed Republican candidate and Civil War hero Ulysses S. Grant in 1868. Grant, who went on to serve two terms, defended the rights of the freed slaves as the Reconstruction period continued. By the early- to mid-1870s, however, the rising bourgeoisie in the North was clearly losing interest in pursuing the goal of racial equality that had featured so prominently with the Emancipation Proclamation and in the early years of Reconstruction. The shift was reflected in the inaction of the federal authorities.

Douglass increasingly accommodated himself to this retreat, working to win votes for Republican candidates by “waving the bloody shirt”—appealing to patriotism and the immense suffering of the Civil War. The man who had helped to inspire a revolution to end slavery now became the occupant of several minor federal positions and a campaigner for every Republican presidential candidate, long after this party of Lincoln had become an increasingly corrupt instrument of big business. Douglass went so far as to defend the Compromise of 1877, the sordid unwritten deal by which Republican candidate Rutherford B. Hayes entered the White House after a disputed election, with the federal government in return withdrawing its last troops from the states of the former Confederacy.

This set the stage for the era of Jim Crow that was to last for generations. When some desperate ex-slaves in the South, called “Exodusters,” attempted to leave for Kansas and the West, Douglass opposed them, claiming as late as 1879 that “the conditions…in the Southern States are steadily improving.” “For the first time in his life, he found himself hissed and shouted down by black audiences,” McFeely recounts.

The shift in Douglass’s outlook can be seen in a comparison of his stands from before the Civil War and afterwards. In My Bondage and My Freedom, Douglass wrote: “The slaveholders, with a craftiness peculiar to themselves, by encouraging the enmity of the poor, laboring white man against the blacks, succeeds in making the said white man almost as much a slave as the black slave himself. The difference between the white slave, and the black slave, is this: the latter belongs to one slaveholder, and the former belongs to all the slaveholders, collectively.” (emphasis in original).

In England in the 1840s, as McFeely reports, Douglass and Garrison met with some of the Chartist leaders who would later collaborate with Marx and Engels. The biographer writes: “In London, Douglas and Garrison made a start at forming the link that Karl Marx always thought was a natural one—between the working classes in Europe, Britain and the American North, on the one hand, and laborers in the American South on the other. It is one of the great missed opportunities of Douglass’s life and of the history of black Americans that this promising effort at cooperation did not bring about a true international working-class movement.”

While Douglass came close to seeing the potential of the working class as a young man, he later left this behind him, especially in the atmosphere of the US Gilded Age. By 1880 he was campaigning for Republican nominee James A. Garfield as “a proud party man,” reports Blight. This was in the immediate aftermath of the bitter strike wave of 1877, but Douglass “had no problem with Republican anti-labor positions…Given the bold-faced white supremacy of the Democrats, Douglass still saw the Republicans as his only political home.”

In his final years, Douglass lived the life of a black elder statesman in the Anacostia section of Washington DC. He remarried after the death of Anna Murray Douglass, to Helen Pitts, a white woman some twenty years his junior, from a prominent abolitionist family, whom he had met when she worked as a secretary in his office as Recorder of Deeds. The marriage met with some opposition both from Douglass’s children and from his new wife’s family as well. Douglass had already endured years of whispered gossip over his close emotional and intellectual relationships with two other women—the British social reformer Julia Griffiths, who spent the first half of the 1850s working closely with Douglass in Rochester; and the German-Jewish journalist Ottilie Assing, who spent more than 20 years in the US, including months at a time in or near the Douglass household. According to Blight, they were probably lovers.

The last decade of Douglass’s life saw him take up the cudgels against rampaging white supremacy. In the early 1890s, inspired in part by the young activist Ida B. Wells, the old man, now well into his 70s, denounced the horrors of lynching.

Douglass died suddenly on February 20, 1895, shortly after returning home from a women’s rights meeting. His funeral service in the capital was attended by dignitaries who included Supreme Court Justice John Marshall Harlan. The casket was taken to Rochester, where Douglass was buried in Mount Hope Cemetery. On the way, he lay in state for two hours at New York’s City Hall.

Many eulogies followed. One of the more noteworthy was from W.E.B. Du Bois, then a 27-year-old college professor in Ohio. As recounted by David Blight, “Du Bois urged students and faculty not to cry out in ‘half triumphant sadness’ at the death of their leader, but to engage in ‘careful conscientious emulation.’ Du Bois remembered Douglass’s leadership in abolitionism, in the recruiting of black soldiers in the war, in the achievement of black male suffrage, and in civil rights. As a leader Douglass had reached for goals considered ‘dangerous’ and all but ‘impossible.’ He was not afraid of the American ‘experiment in citizenship.’ Douglass had proven himself a ‘builder of the state’ largely from outside traditional power. ‘Our Douglass,’ asserted the young intellectual, was the man of the race, but he had also ‘stood outside mere race lines. . . upon the broad basis of humanity.’”

In standing “upon the broad basis of humanity,” Douglass, a lifelong opponent of colonization and separatism, based himself on the democratic ideals embodied in the Declaration of Independence and the Gettysburg Address. He reached a point, however, where his goal of racial equality ran up against the reality of American capitalism and the growing conflict between the rising bourgeoisie and the working class it was itself creating. The movement of the American working class was itself still embryonic. As the gains of the Civil War were eroded by the growth of Jim Crow segregation and white supremacy, Douglass faced a political dead end. His ideals, as we have seen, had become part of the “mainstream” during the Civil War, but the mainstream of the 1890s was very different from that of the 1860s.

Chattel slavery had been abolished but was replaced by the growth of industry and the big cities, and the overwhelming predominance of wage slavery. The defense of racial equality would only be possible by uniting the working class in a common struggle against capitalism. Douglass could not grasp or base himself on the social forces required to deepen the fight for equality. They would emerge more powerfully in the next century, with the struggles of the American and international working class, and above all with the Russian Revolution and its world-historical significance.

Seventy years elapsed between the death of Frederick Douglass and victory against Jim Crow. This was not for lack of opposition to racism, but because segregation could only be overcome through the struggles of the working class, which stretched over decades and were marked by enormous contradictions and difficulties. The mass civil rights movement of the 1950s and 60s stood on the shoulders of the struggles and the gains of the labor movement in the 1930s and 40s.

The efforts in the South were in part inspired by the experiences of millions of workers, both white and black, who had forged bonds in the organizing of the industrial unions, and who had passed through the experience of the Second World War. African-American participants in the Great Migration from the South to the industrial North transmitted a new confidence and militancy back to the movement in the South, which initially took the form of the church-based mass struggles led by Martin Luther King, Jr.

American capitalism has long since repudiated its revolutionary heritage. Two hundred years after Douglass’s birth and more than a century after his death, the cause of social progress is more than ever inseparably bound up with the unity of the working class in the struggle against capitalism, the system of wage slavery. Attempts to stoke racism today can only be defeated as part of this battle. Douglass’s revolutionary legacy has much to teach in this regard, and future generations will remember his enormous contributions.