By David Walsh in the USA:

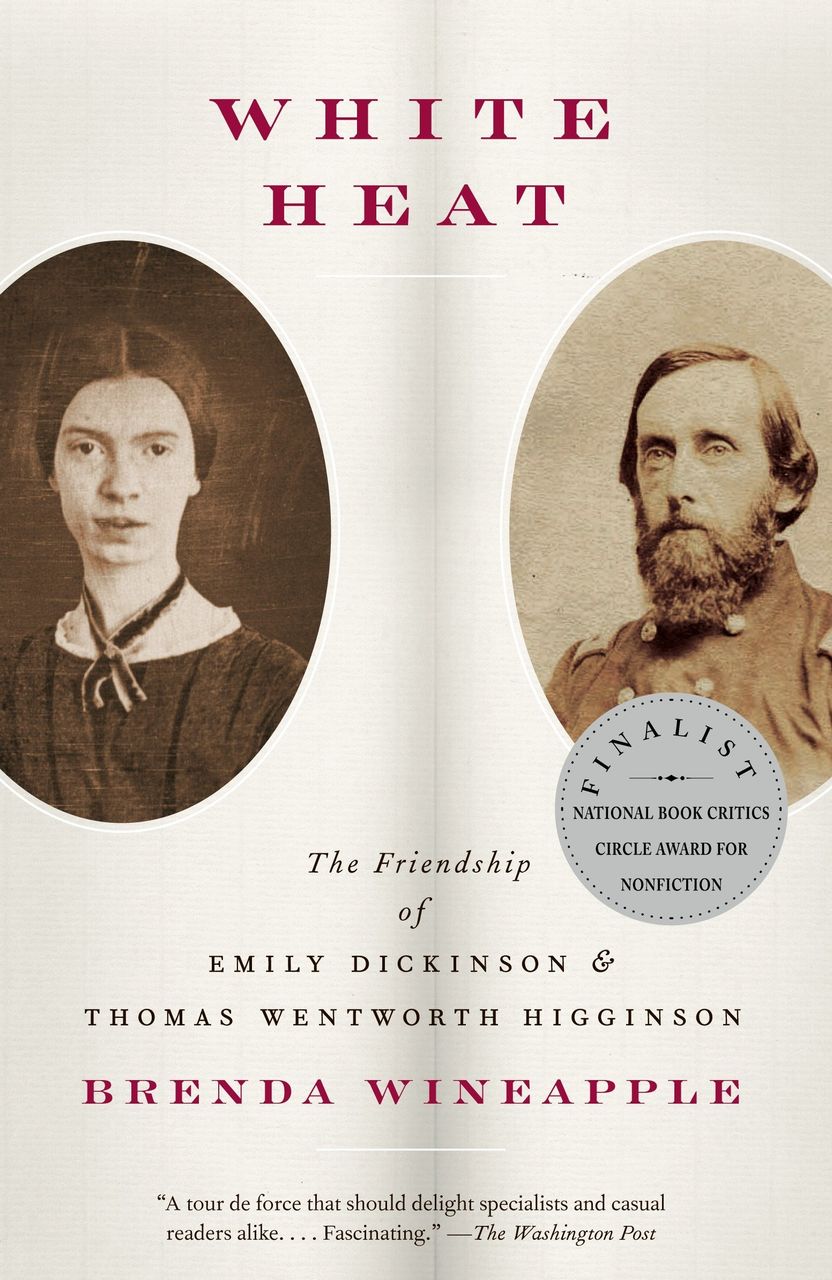

An interview with historian Brenda Wineapple, author of books on Emily Dickinson, Nathaniel Hawthorne and the impeachment of Andrew Johnson

“Writing is a solitary and private act … I’m going to say what I think is true”

13 August 2019

Historian Brenda Wineapple has authored a number of intriguing books about 19th-century American writers and social processes in particular.

We first encountered her work in the process of writing about Wild Nights with Emily, director Madeleine Olnek’s film about American poet Emily Dickinson (1830–1886). Olnek’s work concentrates almost exclusively on Dickinson’s relationship with her sister-in-law, Susan Gilbert Dickinson, depicting an overpowering sexual relationship that is largely (or perhaps entirely) the product of Olnek’s imagination.

We suggested that Wild Nights with Emily was “a largely degrading work that obliterates or trivializes history, demeaning not only Dickinson, but also, in passing, the remarkable abolitionist and literary figure Thomas Wentworth Higginson.”

Olnek, for reasons of her own, chooses to transform Higginson into a self-important, condescending, repressive cartoon male, who simply doesn’t “get” Dickinson.

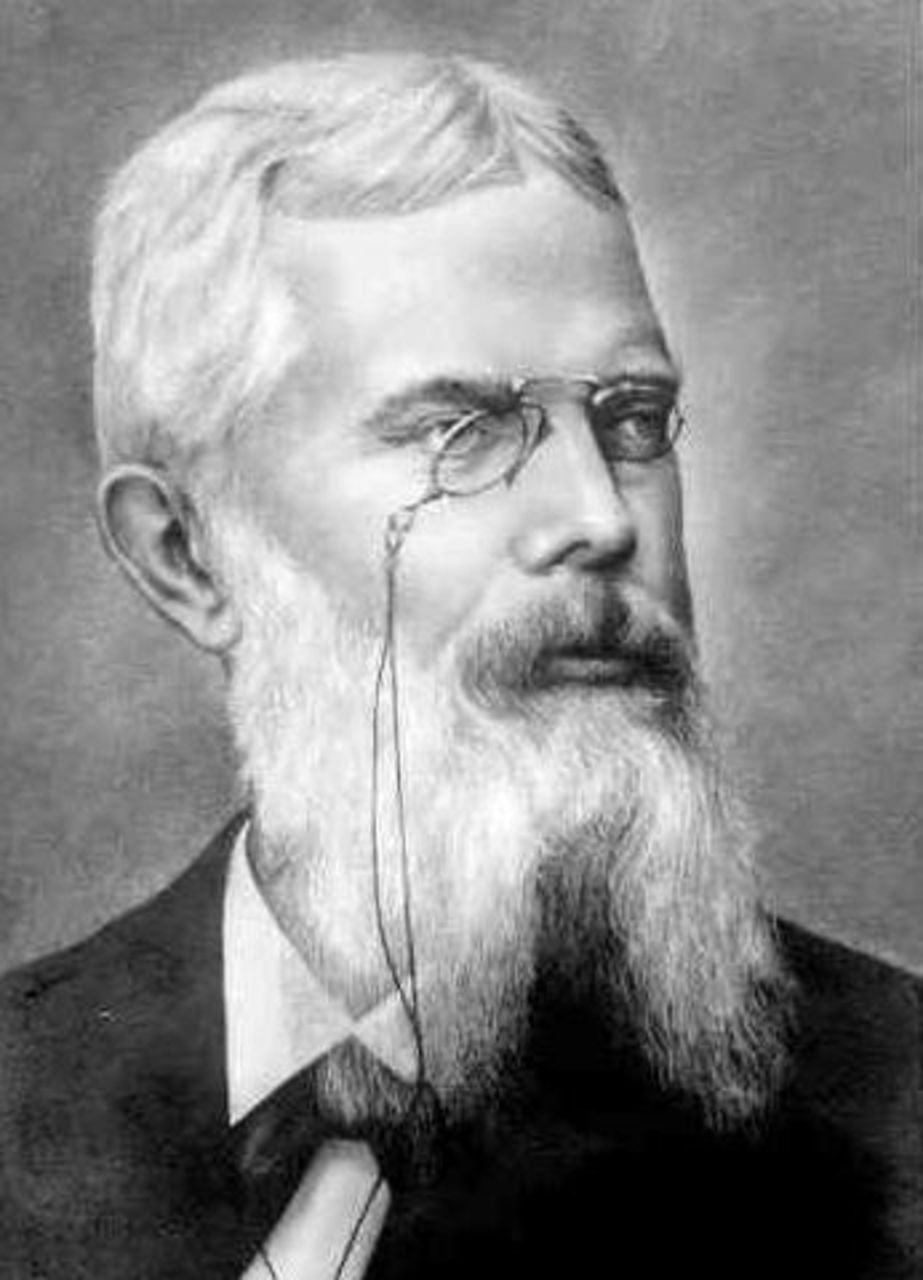

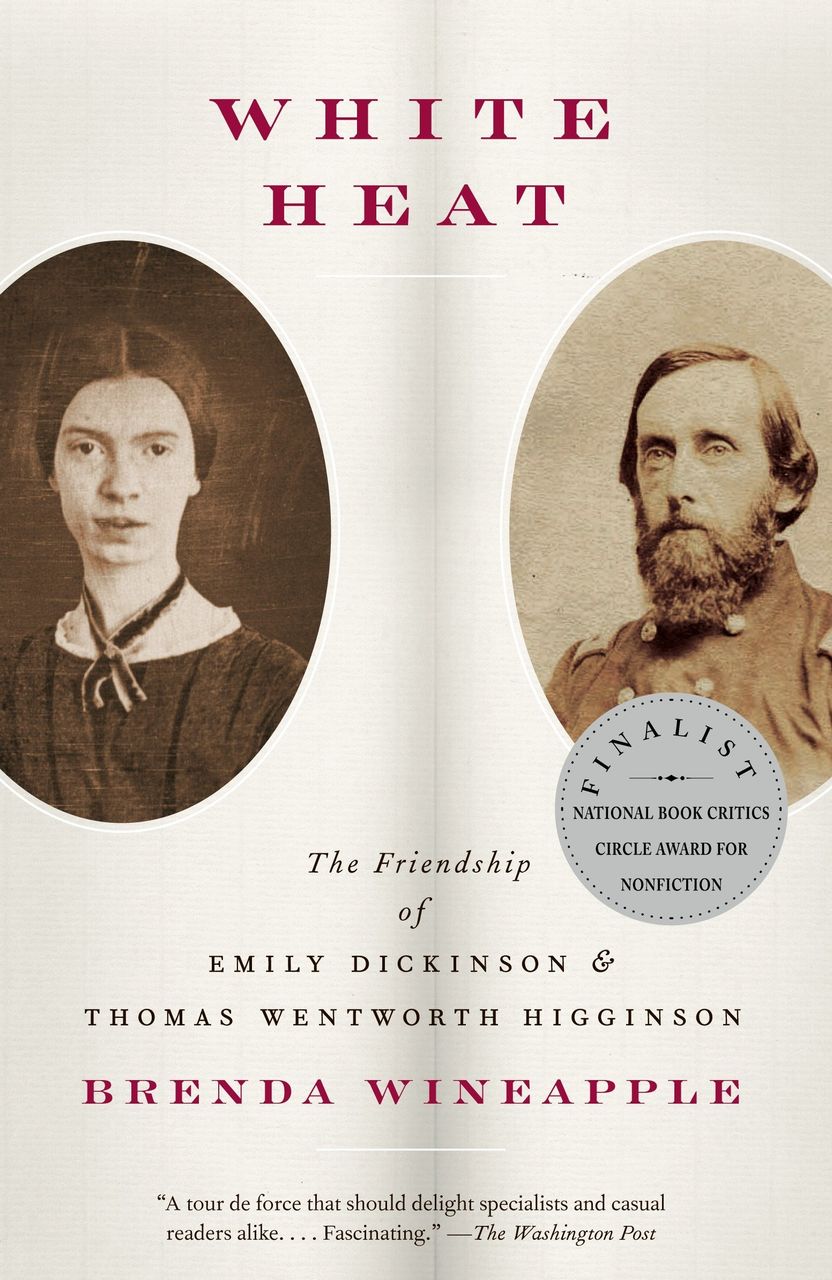

Wineapple’s White Heat: The Friendship of Emily Dickinson and Thomas Wentworth Higginson (2008), a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle award, arrived as both an antidote and a breath of fresh air. The book deals meticulously and honestly with the contradictions and peculiarities of the mid-19th century period, the milieus to which Dickinson and Higginson belonged, and their personalities and trajectories. It pays tribute to Higginson’s remarkable activities and concerns, including his support for abolitionist John Brown, while noting at the same time, that he was a “man of limits, to be sure,” who “was gifted enough to sense what lay beyond him,” i.e., the full significance and originality of Dickinson’s poetry.

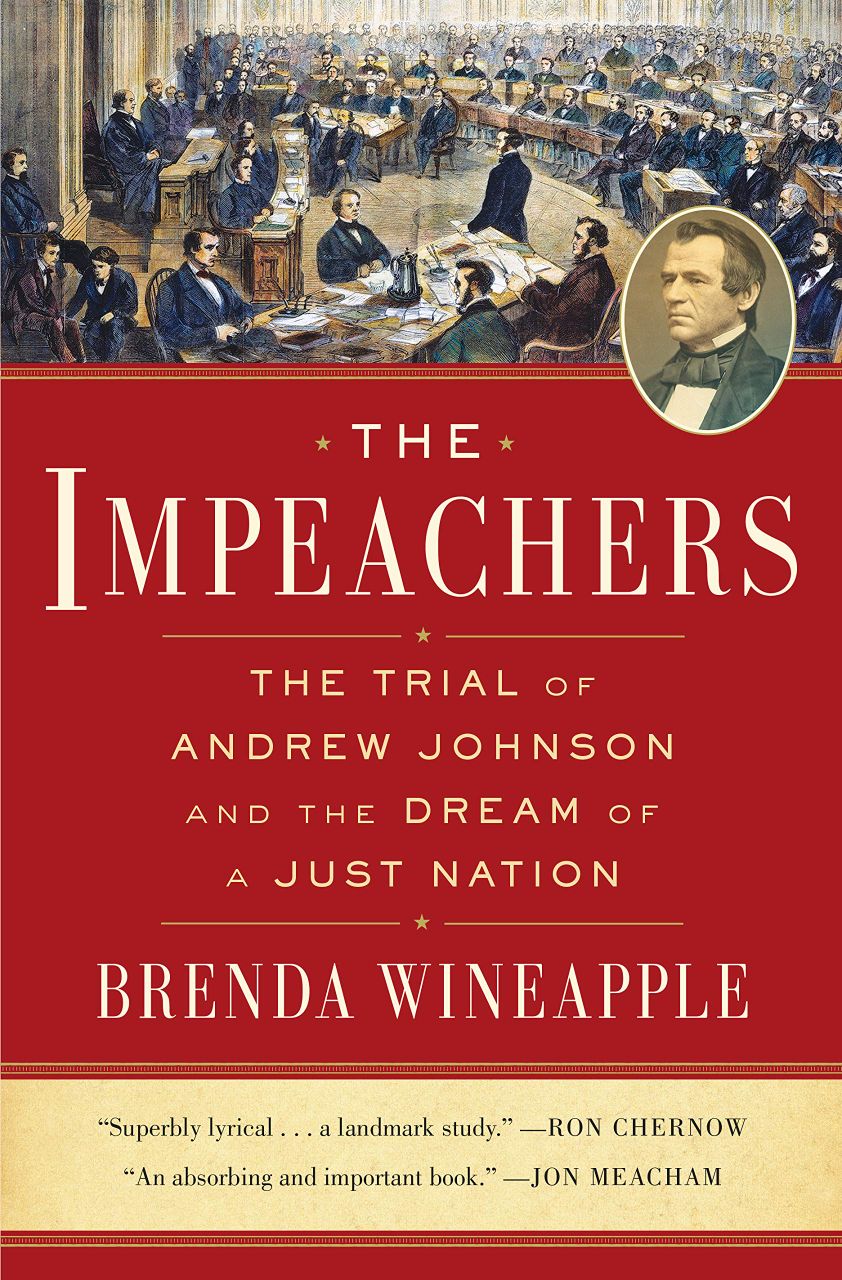

The honesty and objectivity of Wineapple’s approach in White Heat finds expression as well in The Impeachers: The Trial of Andrew Johnson and the Dream of a Just Nation (2019). Coincidentally, the WSWS reviewed the book in June, only a few weeks after the comment on Wild Nights with Emily appeared.

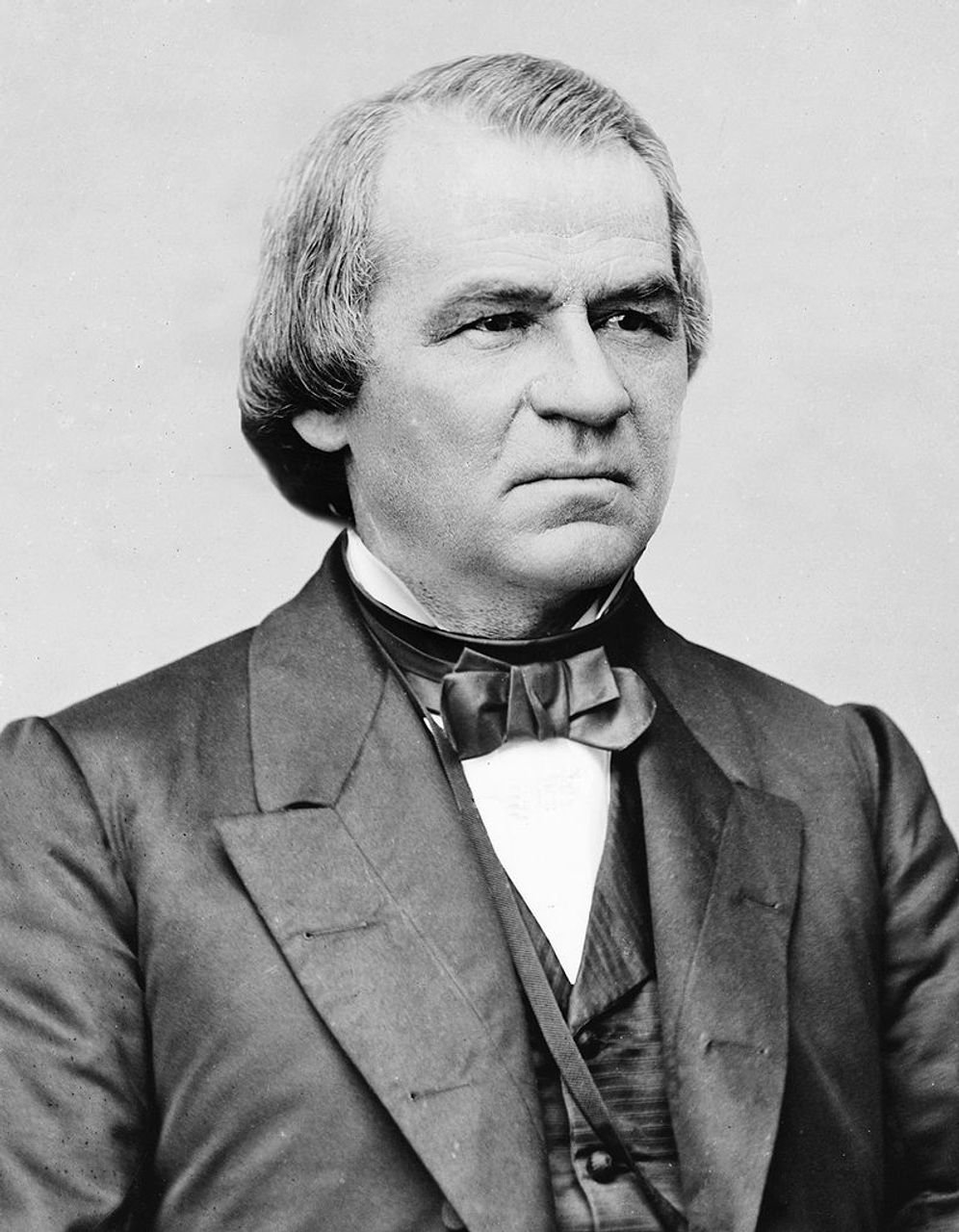

The Impeachers treats the effort in 1868 to remove President Andrew Johnson, who had assumed office upon the assassination of Abraham Lincoln in April 1865, because of Johnson’s anti-democratic and illegal efforts to defend the remnants of the slavocracy and defy the attempt by Congress to reorganize the rebel states to protect the former slaves.

Analysis of Johnson’s impeachment, as Eric London explained in his review of Wineapple’s book, “has long been dominated by apologists for the slavocracy who claim that the trial was led by vindictive radicals to punish Johnson for seeking ‘compromise’ with the former rebels. … Wineapple takes aim at the notion that the impeachment of Johnson was merely an example of ‘hyper-partisanship.’ She has written a book that cuts through the lies of the Lost Cause and Dunning School of historians.”

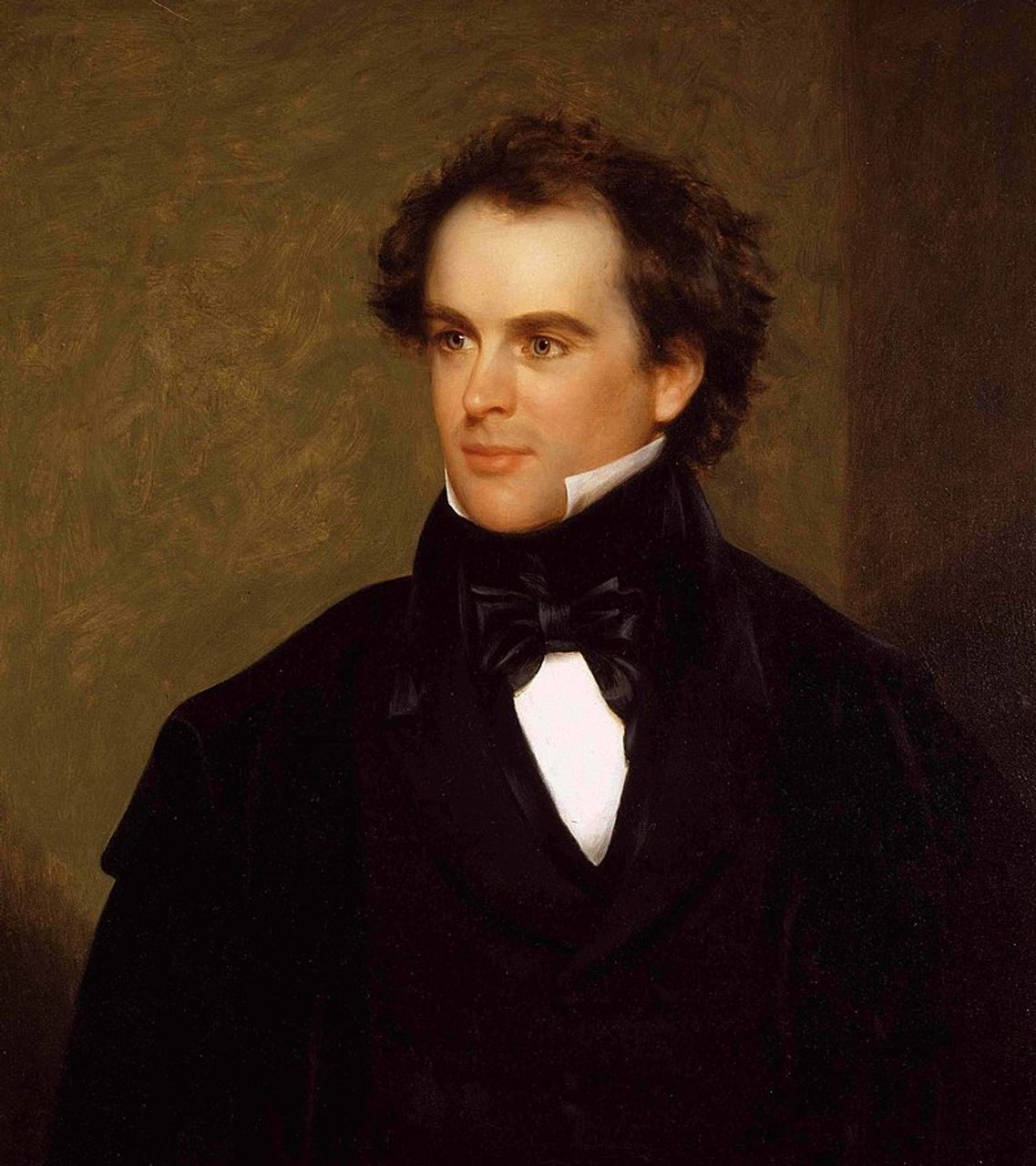

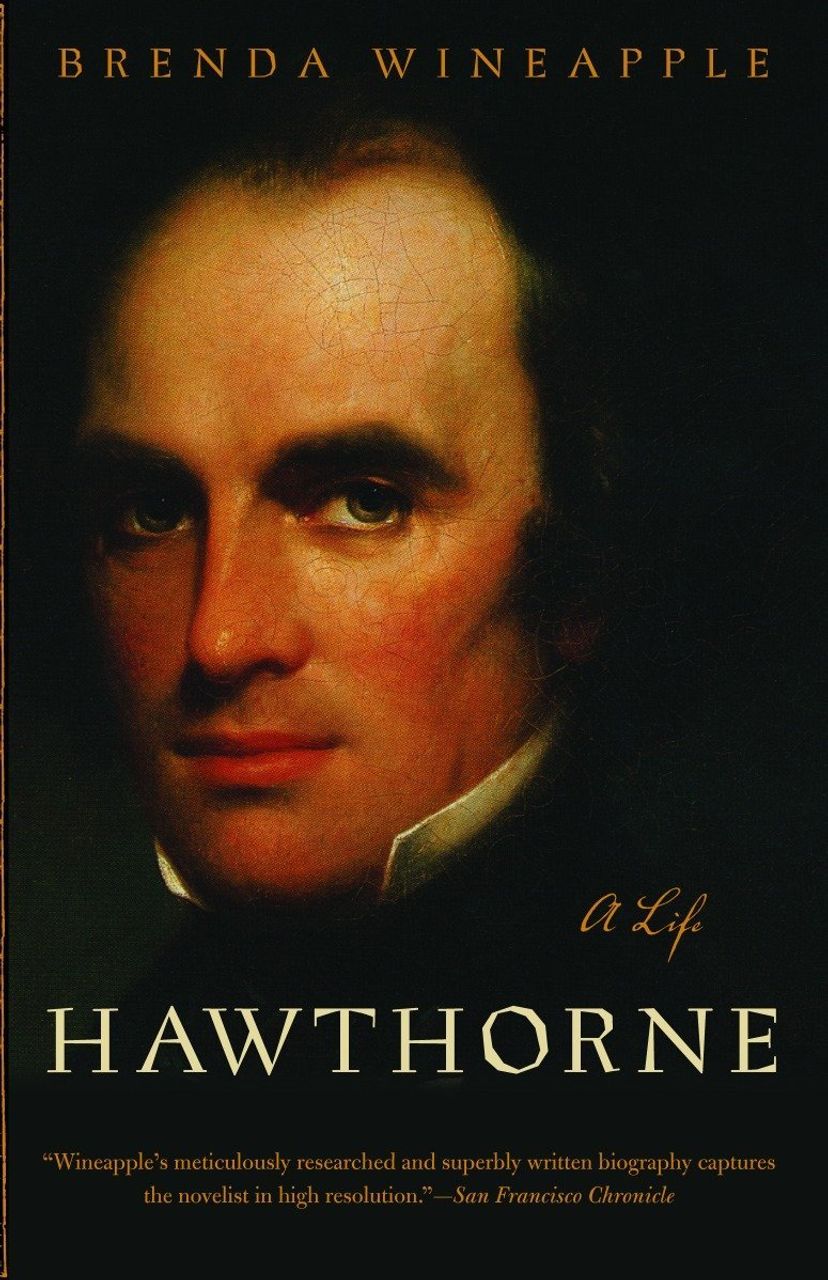

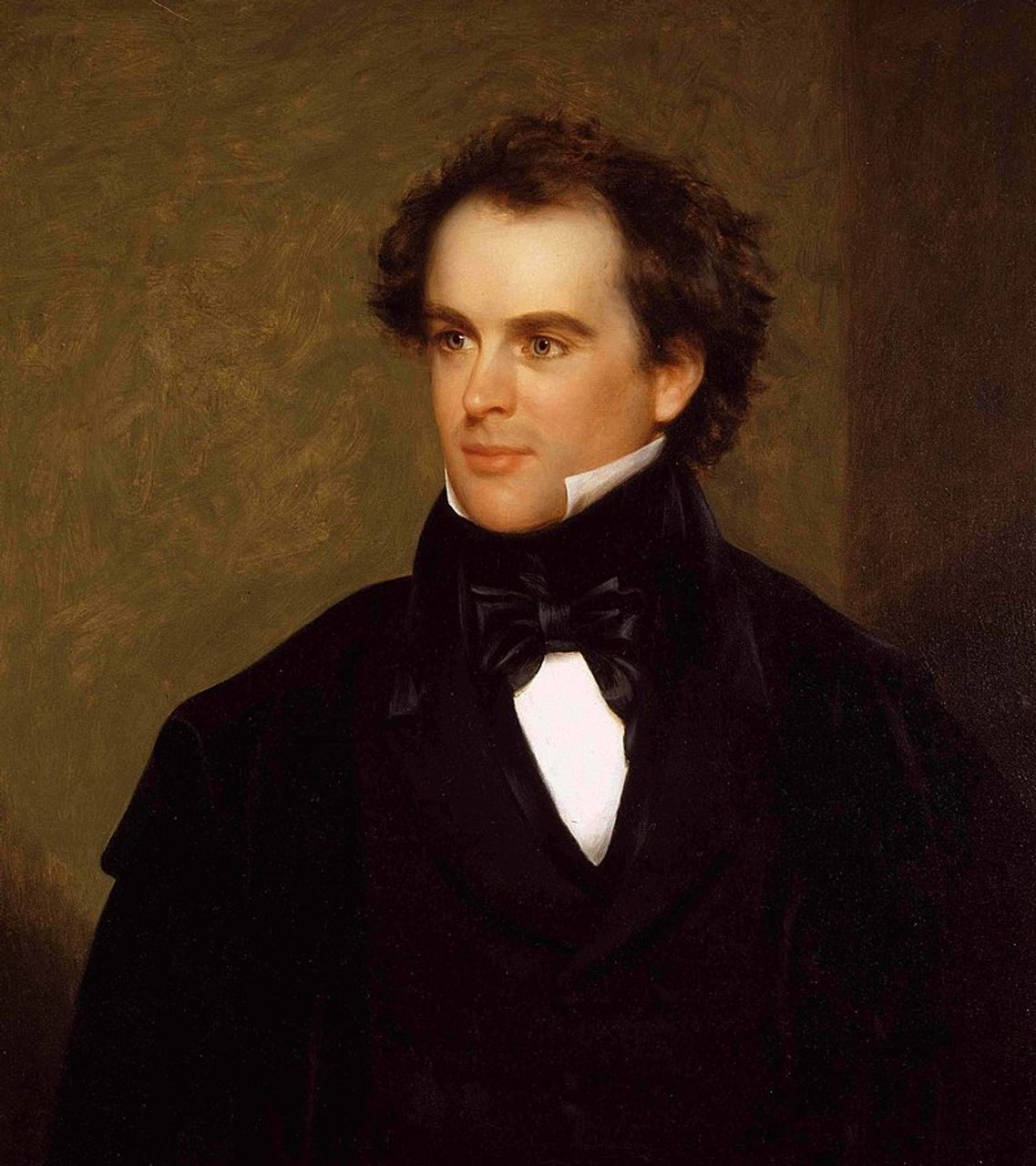

Wineapple has also written Hawthorne: A Life (2003), a major biography of the great American writer Nathaniel Hawthorne, responsible for The Scarlet Letter (1850), The House of the Seven Gables (1851) and The Marble Faun (1860).

She is the author as well of Genêt: A Biography of Janet Flanner (1989); Sister Brother Gertrude and Leo Stein (1996); and Ecstatic Nation: Confidence, Crisis, and Compromise, 1848-1877 (2013). Wineapple edited The Selected Poetry of John Greenleaf Whittier (2004) for the Library of America and the anthology, Nineteenth-Century American Writers on Writing (2010).

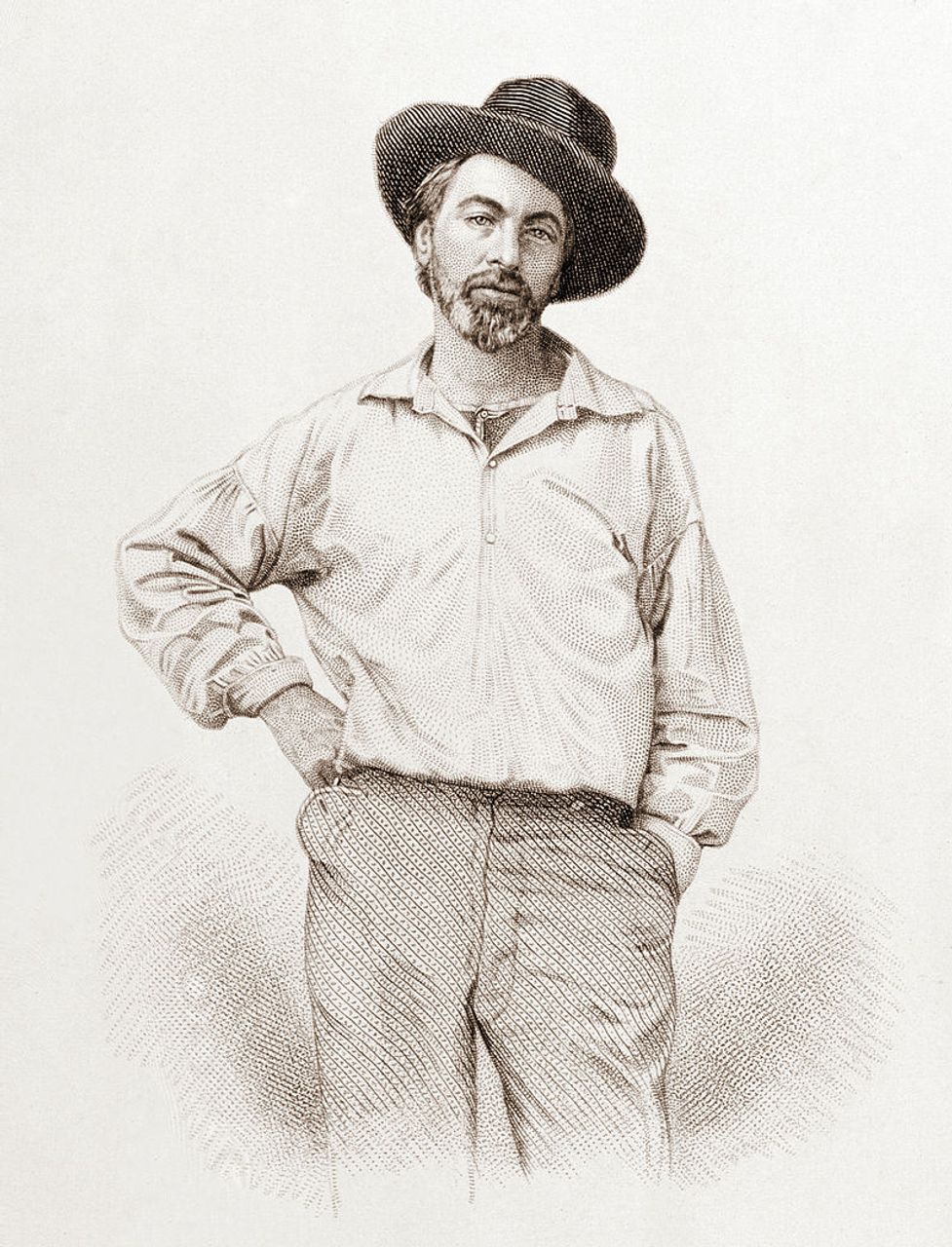

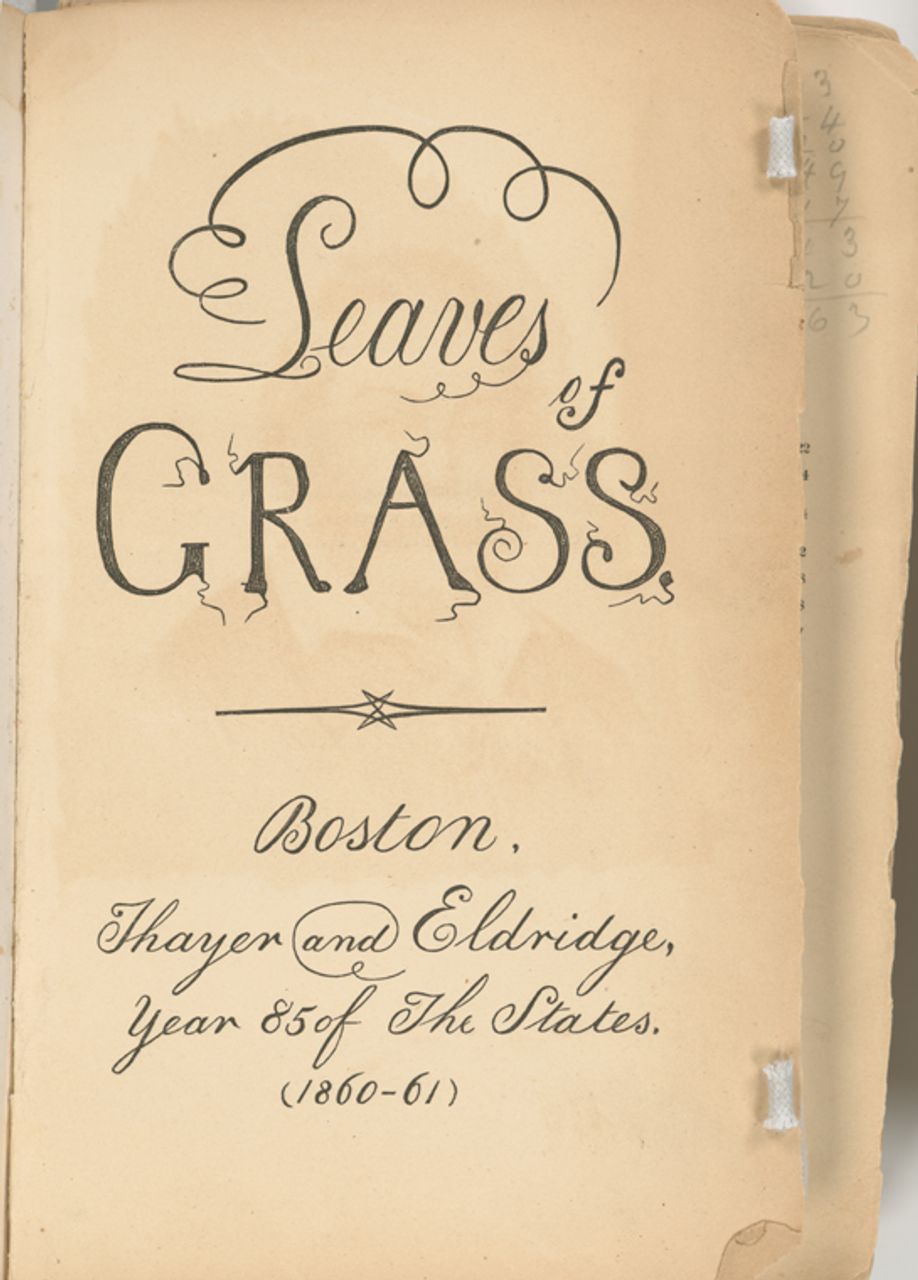

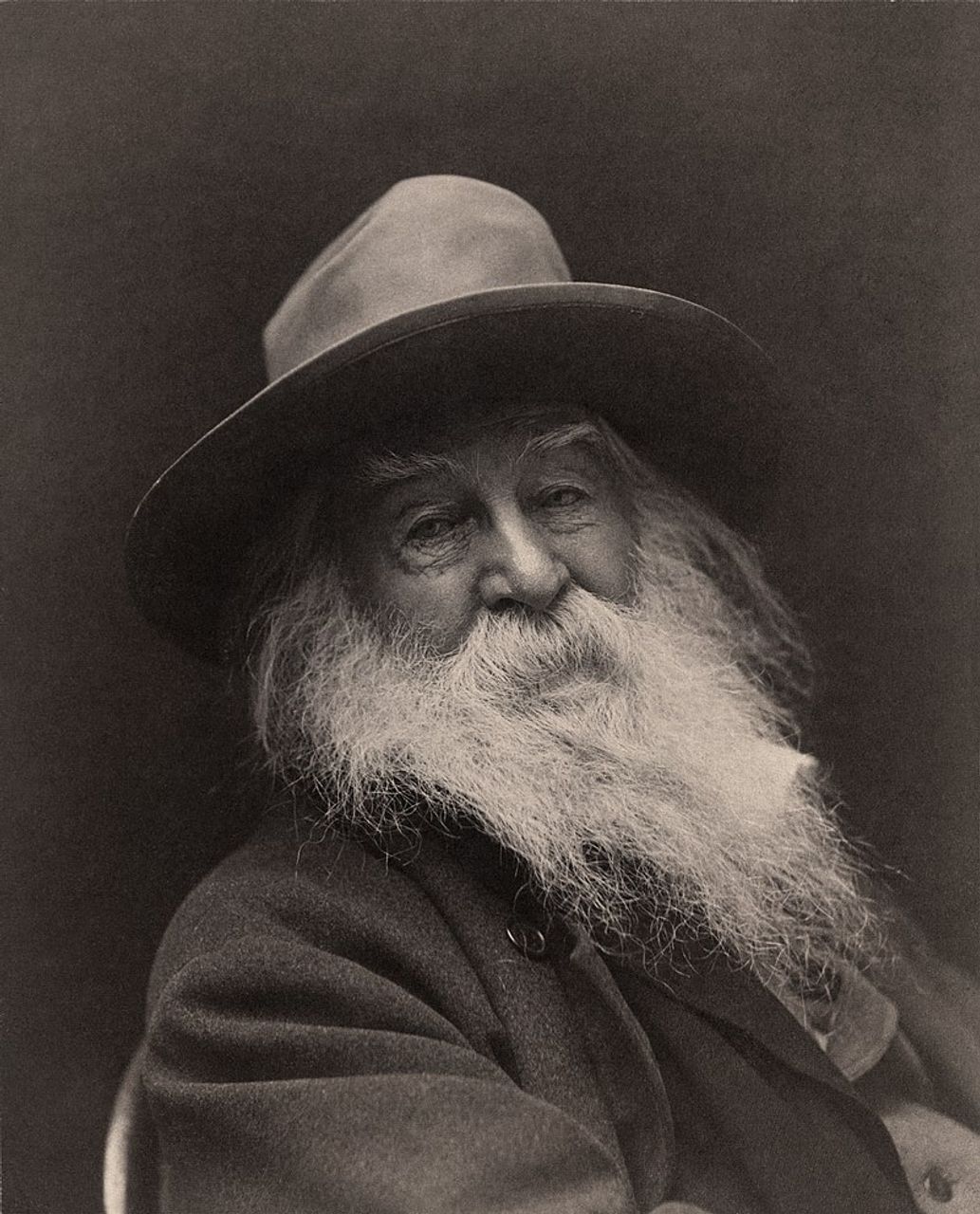

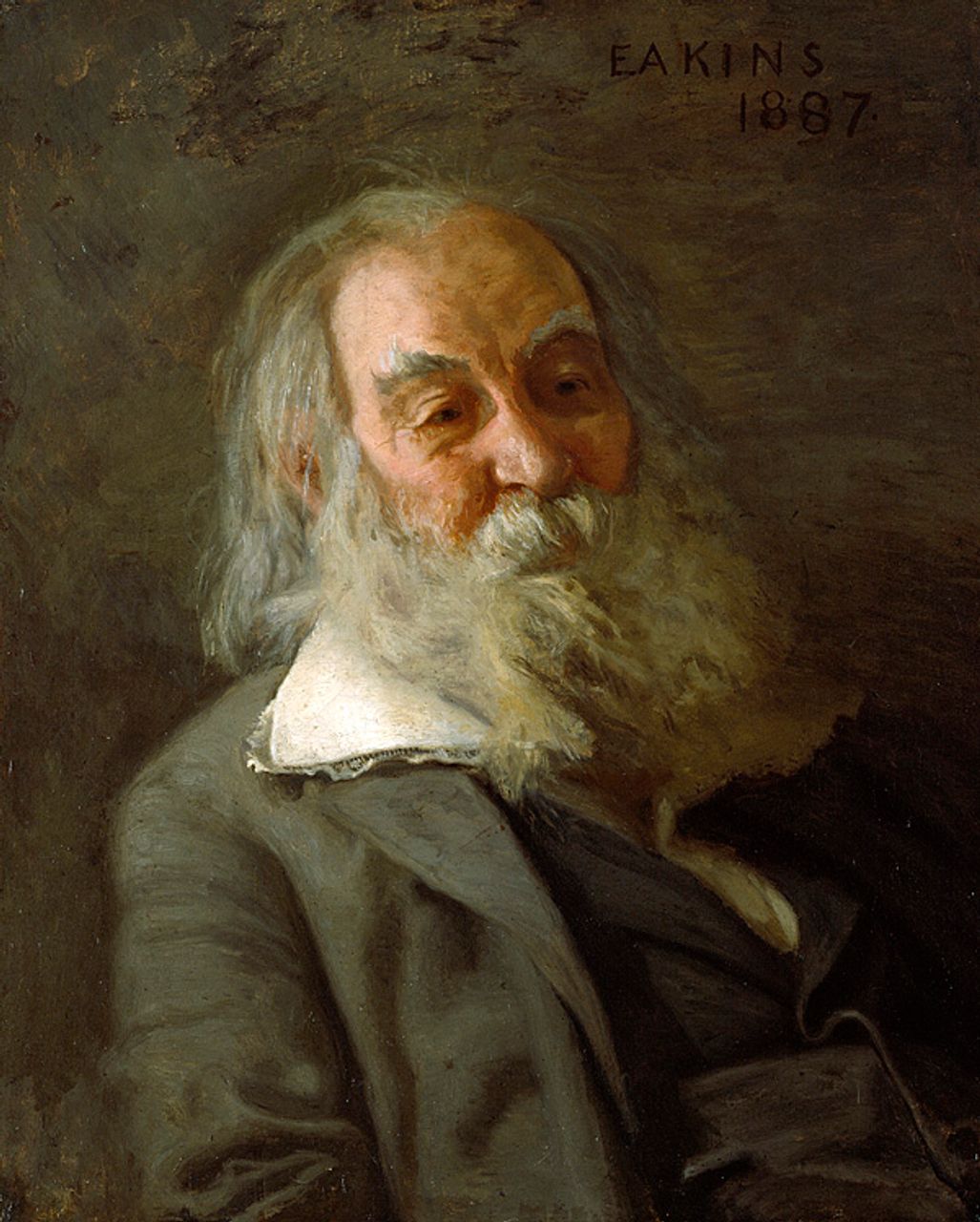

In addition, Whitman Speaks, her selection of the poet’s observations about writing, literature, America and what it means to be a maverick was published last spring in celebration of the bicentennial of Whitman’s birth.

Wineapple’s numerous honors include a Literature Award from the American Academy of Arts and Letters, a Pushcart Prize, a Guggenheim Fellowship, an American Council of Learned Societies Fellowship, two National Endowment Fellowships in the Humanities, and most recently an NEH Public Scholars Award. She is an elected member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and of the Society of American Historians and regularly contributes to publications such as the New York Times Book Review and the New York Review of Books.

Born in Boston and a graduate of Brandeis University, Wineapple teaches at the New School and Columbia University in New York City.

We spoke recently on the phone about a number of issues raised in her books. Eric London contributed the questions about The Impeachers.

* * * * *

David Walsh: This all began with a foolish movie, Wild Nights with Emily, which I suppose I do have to thank, in fact, for directing me toward Emily Dickinson and Thomas Wentworth Higginson and toward your remarkable book, White Heat.

I’m not going to put you on the spot about the film, but I hope the article indicated its unconvincing … character. In general, it seems to me contemporary artists have a much weakened “historical sense”, the ability to imagine social conditions and relationships different than their own.

Brenda Wineapple: Well, yes, if you actually looked more deeply into the past you wouldn’t have to foist contemporary views onto it. You could tease out perspectives; you could indicate how the past flows into and resonates today rather than superimpose contemporary attitudes and ideas on it. To do that suggests a lack of historical imagination, as you say, which is a problem.

DW: Emily Dickinson comes across as a brilliant figure, an almost terrifying figure. I say this half-jokingly, but when Higginson says, “I am glad not to live near her”, you wonder a little if she secluded herself in Amherst, Massachusetts not to be protected from other people, but to protect them from her.

BW: I really do feel that Higginson’s comment has been misread. It’s not that he couldn’t handle her, but rather that Dickinson was one of those people who was really exhausting; she took everything out of you because she was on fire, so it must have been enervating just to keep up with her. “She drained my nerve-power”, as he said. Her astonishing inventiveness, her quickness, her vision permeate not just the poetry but her letters, which are simply astonishing. So imagine what she must have been like in person.

And don’t forget that Higginson was a very unusual figure, given the times during which they both lived. Of course he wasn’t perfect, and he certainly wasn’t the genius Dickinson was, but that’s not the point. He was a committed abolitionist—and activist—during one of the most tumultuous and dangerous decades in American history.

DW: Your book does a great deal to resurrect or restore both figures, Higginson in particular. Dickinson is probably not in need of it, anyway.

BW: It seemed fascinating to me that you had these two characters, two individuals, not simply alive at the same moment but who formed a friendship that was important to both of them and lasted almost twenty-five years, right to the end of Dickinson’s life.

DW: Did you set out to do this, resurrect Higginson, or was this a need you discovered in the course of your research?

BW: I came to this book with a set of questions. I’ve always admired Dickinson and I had the conventional view of Higginson: he bowdlerized her, he ruined her poetry, he didn’t get her. But then I wondered why she was friends with him. And then I thought, if we admire her, which we do, if we think she was so perceptive, so brilliant in so many ways, then why don’t we look more carefully at her choice of friends? Because she chose so few. So she must have seen something in him that we didn’t see. So I began with those kinds of questions. So I didn’t set out to resurrect or restore him but to discover what we could learn about this man that would respect her choice.

Of course I knew something about Higginson because he was adjacent, so to speak, to the book I did on Nathaniel Hawthorne. He was of the same world, although Hawthorne would not have had anything do with him because of their different politics. And I’d done a little edition of John Greenleaf Whittier’s poetry, and Whittier was himself a committed abolitionist, so he and Higginson sort of overlapped historically and therefore I’d heard of him apart from Emily Dickinson.

DW: When Dickinson wrote to Higginson: you saved my life, how do you take that? She wasn’t just flattering him.

BW: I don’t think so. Of course, she could be very coquettish, to use a 19th-century word. She wasn’t lying. She was hyperbolic though. I think she meant that he gave her something that no one else was really able to.

DW: What do you think that was?

BW: It’s hard to know. Dickinson constantly wanted him to come to visit her in Amherst. Even though she knew he didn’t entirely understand her poetry, she must have respected him. And he was some sort of representative as well of the outside world, while she penetrated the interior world, “where the meanings are”, as she once wrote. And then to use a trite word, Higginson represented a kind of “otherness” that she must have perceived she shared with him. Neither of them, in their very different ways, represented the status quo.

But it is very difficult to know precisely. We don’t have a lot of his letters to her. We have enough, but not that many. So perhaps he provided a kind of empathy that had nothing to do with his in-depth understanding of the poetry. But he appreciated it—and her. He knew she was a genuine maverick, and she knew he knew.

Plus, let’s not forget Higginson was an unusual guy. He was so enamored of [Henry David] Thoreau’s A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers [1849] when he received a galley that he took a train up to Concord to see Thoreau. Who does that?

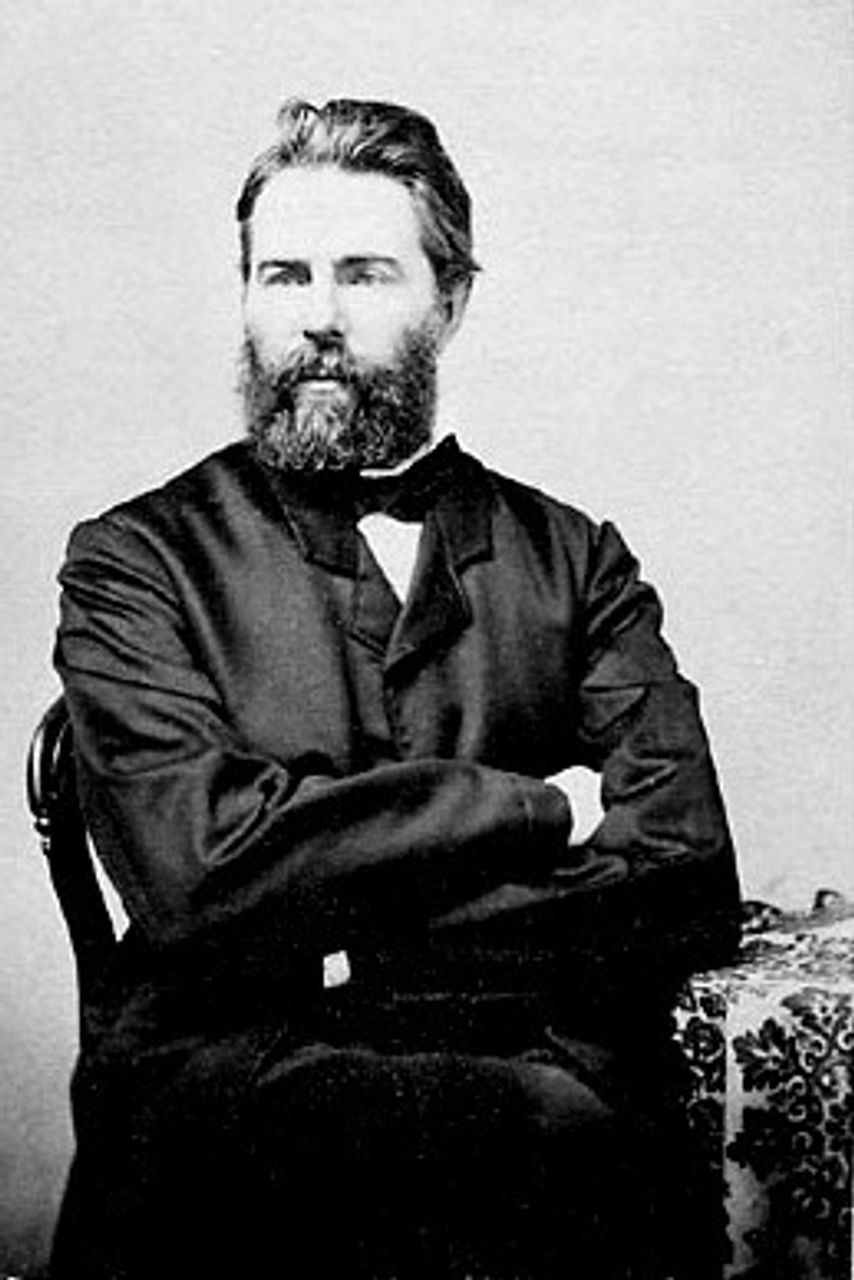

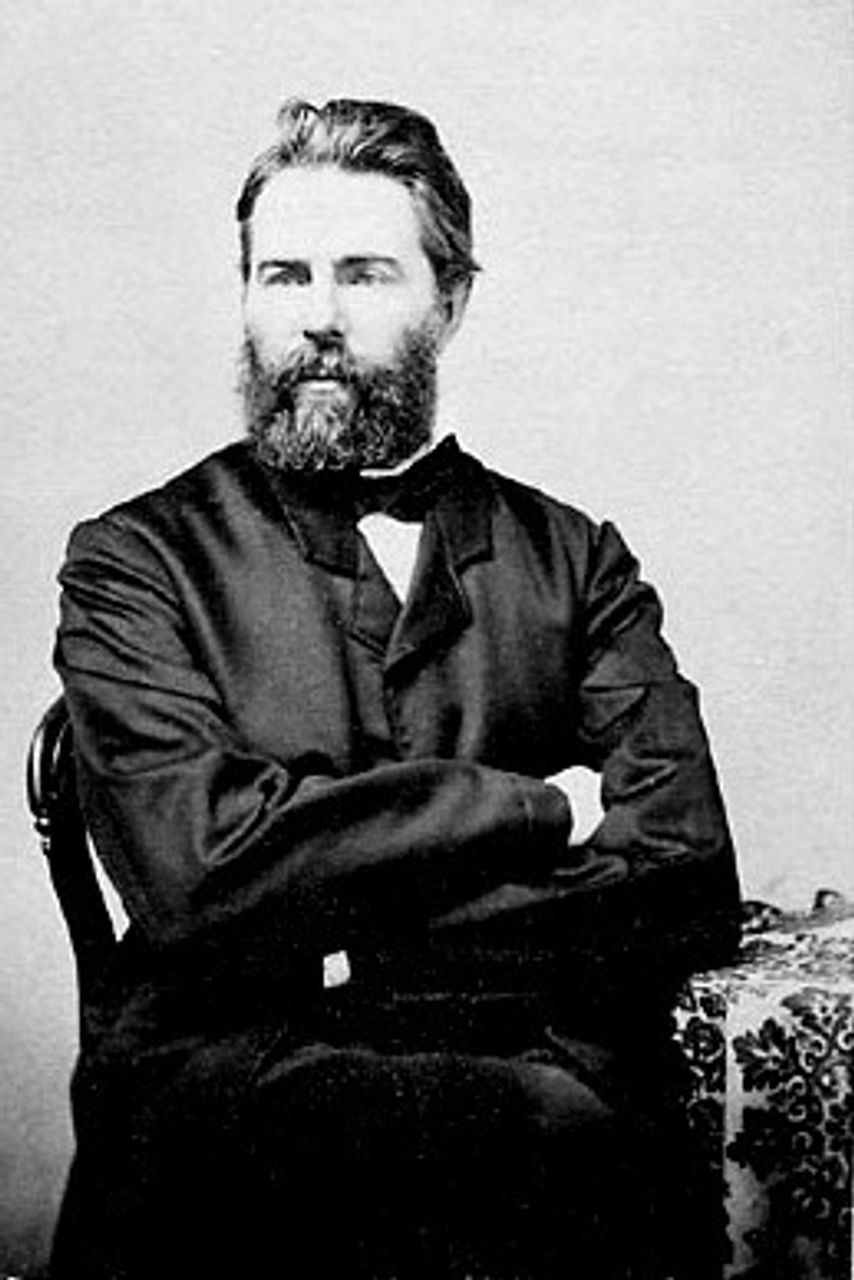

DW: The relationship of artists to social life and to great events like the Civil War is very complex. Higginson’s relationship to the Civil War, of course, is quite clear. The cases of [Ralph Waldo] Emerson and Thoreau too are pretty clear-cut, Walt Whitman as well perhaps. The relationship of Dickinson, Hawthorne, Herman Melville to big events is more oblique. But I don’t think Dickinson was removed from her period of history. And I can’t help but think that was part of her interest in Higginson.

BW: Absolutely. She knew who he was. He was writing about slave revolts, writing very radical pieces in the Atlantic. Her family received the Atlantic. She read his pieces. These writers were very connected to what was going on historically. To suggest that Dickinson had no consciousness of the Civil War is just silly. Her father had been in Congress. He was bringing that home all the time. I don’t know how you could not be conscious of that.

Hawthorne is another case. He was a close personal friend of Franklin Pierce, the future president, who is a horror from our point of view. Hawthorne really loved the guy, and dedicated a book to him. Emerson was so disgusted that he tore out the dedication in his copy of the book. We don’t know enough about Melville because many of his papers are gone. In his book of poems, Battle-Pieces [1866], Melville has an afterword in which he speaks, to put it simply, about forgiving the South. He was also a lifelong Democrat. Whitman was too.

DW: In terms of Dickinson—during what other period could a poet, a supposedly dainty poet, have written the line, “My Life had stood—a Loaded Gun—”?

BW: She’s thinking about guns!

DW: An incredible line, which you suggest may have been inspired by Higginson’s essay about the Nat Turner slave revolt.

American literature reached a new height in the pre-revolutionary decade of the 1850s. Have you thought about what it was and how it was that artists were working with such intensity and urgency in the period before and perhaps during the Civil War? In any case, something was sending off powerful impulses.

BW: I definitely think so. Dickinson wasn’t active, so to speak, in any conventional sense. But you could say she was in some way seeing Higginson’s activity as an extension of herself.

DW: Exactly. He was in some way her representative in that other, more public world. She was such a powerful personality that I think she was hoping—and I don’t mean this in a negative way—she could will him, direct him in some way. And probably she did!

BW: He did have to resist her somewhat. As we said, her magnetic force was huge. But it’s interesting that after he wrote the essay, “Letter to a Young Contributor,” in the Atlantic magazine [in April 1862], he received a huge number of letters; Dickinson wasn’t the only person reaching out to him. But she was the only one he really responded to.

DW: Nathaniel Hawthorne is another remarkable figure. Politically, he certainly isn’t attractive. A Democrat and no friend of the abolitionists. But a brilliant writer. The Scarlet Letter and The House of the Seven Gables are milestones.

BW: He was a brilliant writer. Someone said, “Hawthorne can see in the dark.” He really could. But, to go back to the issue of lacking a historical sense, we also have this almost childish wish to make the writers that we think of as remarkable, as in the case of Hawthorne, conform to whatever our historical, political, social principles happen to be. And he doesn’t.

DW: Art and social life have a very complicated relationship.

BW: Hawthorne was most comfortable being by himself, writing, and yet his friends were people involved in politics and, in many cases, Southern-sympathizing politics: John O’Sullivan, to an extent Horatio Bridge, and of course Franklin Pierce. These were dear friends.

DW: Coming out of that history of Puritanism and severity in Salem, and then reflecting on it so intensely and self-critically, it’s not so odd that he was tortured. It would be odd if he weren’t.

BW: I’m from New England too. You can’t get out of there without being tortured.

DW: They’re very different, but both Dickinson and Hawthorne have this profound attachment to the past, they’re immersed and embedded in the past, to a certain extent, but something in the future is also pulling them very strongly.

BW: I think that’s absolutely true. This pull—of the past and of the future—creates a tremendous conflict for them but also, perhaps, a rewarding and enriching one.

DW: You have these very lovely sentences: “Had Hawthorne squeezed refractory emotions into channels much too narrow? No: those channels helped to create emotion by harnessing what they unleashed.” Could you perhaps explain them a little?

BW: I think it’s precisely what we’re talking about. With Hawthorne, there was a terrible conflict, a sense that he was almost destroyed by what made him great. He was able to use it, up to a point, but again it was also so depleting in many ways and he had to channel it into a form that was almost 18th century in style that then recreated this emotion for the reader.

DW: You also point to the utopian, visionary element in Hawthorne, passages where he sounds downright revolutionary. There’s this in The House of the Seven Gables that struck me: “[Holgrave] had that sense, or inward prophecy … that we are not doomed to creep on forever in the old bad way, but that, this very now, there are the harbingers abroad of a golden era, to be accomplished in his own lifetime. It seemed to Holgrave … that in this age, more than ever before, the moss-grown and rotten Past is to be torn down, and lifeless institutions to be thrust out of the way, and their dead corpses buried, and everything to begin anew.”

This quasi-revolutionary vision of tearing down the past, thrusting institutions out of the way and so forth is immediately followed by a wretched argument for gradualism and fatalism:

“His [Holgrave’s] error lay in supposing that this age, more than any past or future one, is destined to see the tattered garments of Antiquity exchanged for a new suit, instead of gradually renewing themselves by patchwork; in applying his own little life-span as the measure of an interminable achievement; and, more than all, in fancying that it mattered anything to the great end in view whether he himself should contend for it or against it. … He would still have faith in man’s brightening destiny, and perhaps love him all the better, as he should recognize his helplessness in his own behalf; and the haughty faith, with which he began life, would be well bartered for a far humbler one at its close, in discerning that man’s best directed effort accomplishes a kind of dream, while God is the sole worker of realities.”

BW: It’s interesting, because it’s exactly what Hester Prynne feels in the thirteenth chapter of The Scarlet Letter, “Another View of Hester”, which I write about.

Hester essentially thinks, everything needs to be torn down and the relationship between men and woman has to start all over again to be effective, just and fair both to women and to men. It’s an enormously radical vision. And she’s part of Hawthorne since he created her. But then, to a certain extent, he punishes her, precisely for having that vision. In the same way, he sends Holgrave off to this pointless future, marrying Phoebe and living happily ever after—which I don’t believe Holgrave does.

That is, Hawthorne was attracted, almost violently, to this vision of a new world, which by the way was very much in the air. Bronson Alcott and others were talking about or planning or trying actually to live this new world. But then Hawthorne condemns it in his novel The Blithedale Romance [1852], which was about the Brook Farm experiment.

DW: The honest artist is not simply the sum-total of his social and political views. You write: “Of all writers, female or male, in nineteenth-century America, Hawthorne created a woman, Hester Prynne, who still stands, statuesque, the heroine par excellence impaled by courage, conservatism, consensus: take your pick. Yet there she is.”

BW: It’s kind of astonishing.

DW: We don’t remember or value Hawthorne because of his seedy dealings with the Democratic Party, with Pierce, we remember him because of that, because of Hester Prynne and the others he created—or discovered.

BW: That’s his real, objective contribution to us. The irony is that he made this contribution, this statuesque and strong woman, almost against his will. He wants to create her, and then doesn’t quite want to. But the truth is that nobody in American fiction is quite like her.

DW: I also have a few questions about The Impeachers. Can you tell us a little more about the political program of Senator Ben Wade from Ohio and his career following the failed effort to remove President Andrew Johnson in 1868?

BW: Wade, of course, was singled out by Karl Marx because he was the radical of radicals, who then more or less disappeared from our consciousness. Other radicals such as Charles Sumner and Thaddeus Stevens disappeared to a certain extent too, but not entirely. But in the late 1860s, and certainly beyond, an emerging conservatism erased Ben Wade. And don’t forget that by 1868 he had lost his Senate seat.

Wade was born, I believe, in 1800, so he was 68 by this time, which was considered rather old then. In 1868, he went back to Ohio, because his term in the Senate was at an end. But Wade had been a tremendous force in Congress—and even one of the reasons that an impeached Andrew Johnson was acquitted. People were afraid of Wade. Given Lincoln’s assassination, if Johnson, his replacement, had been convicted in the Senate, Wade, as president pro tempore of the Senate, would have become president for the remainder of Johnson’s term.

With the failure of the impeachment of Johnson, it not only became clear Wade was not going to be president, but neither did he really have a shot at being vice president on the Grant ticket, which he probably would have had if impeachment had succeeded. At that point, he no longer had a political career or a political future.

Wade scandalized many people. He was so radical that he actually thought women should have the vote. Hah! In my book I mention that one of the “terrible” rumors circulating was that if Wade were in the White House, he might put Susan B. Anthony in his cabinet. That horrified certain people.

DW: How did the impeachment process and its fallout change the political character of the two parties, if it did?

BW: It definitely changed the character of the Republican Party. The group of moderate Republicans, who initially supported impeachment but who then backed away from it, became the core of what was called the Liberal Republican Party, formally organized in 1872.

The Liberal Republican Party, as opposed to the Radical Republicans, was the forerunner of today’s Republican Party. They were an elite group who believed they were the best men in the country, and the government should only be run by the best men. They considered that they knew best. They hated Ulysses S. Grant, whom they regarded as both a radical—and an embarrassment. They were much more content with Rutherford B. Hayes in the White House, which promised the end of Reconstruction.

These Liberal Republicans were the basis for the free-market Republican Party that we know today. For not until later did the Democratic Party become the modern Democratic Party. The Democrats of the 1850s and ’60s … it’s almost unthinkable what they represented, which for many of them was a continuation of slavery or the perpetuation of its noxious legacy. Yet Andrew Johnson was toxic to them; they weren’t going to nominate him in 1868, for sure. But they nominated two candidates, one of whom was a non-entity, Horatio Seymour, governor of New York, and then the other, for vice president, one of the most outspoken and violent white supremacists of his era, Francis Blair of Missouri. Blair’s rhetoric out-Johnsoned Johnson. They went down to defeat, fortunately. Grant won.

The Democrats didn’t reconstitute themselves for years. Or perhaps they never did entirely, because it was always the southern Democratic wing that was very much in power in the party up until the middle of the 20th century.

DW: In our review, the WSWS emphasized the significance of the emergence of the working class as a political force and its impact on American politics during this period. Were the personalities in your book aware of this?

BW: Many of them didn’t live that long. In many cases, they didn’t outlive this immediate era, the era of the Civil War. Obviously, to someone like Thaddeus Stevens and Ben Wade, the relationship between capital and labor, if you want to use those terms, had to change once you no longer had slavery. Because wage slavery had been an issue from the 1850s up until the war; in fact the exploitation of wage laborers was a Democratic Party argument against the Republicans: you can’t talk about slavery as exploitation; we treat the slaves well, but it’s factory workers who are exploited. So the radicals were aware of the labor question but not so much in terms of what was to occur in the cities or with the rise of the railroads, in particular, especially after the war, which really changed everything. They didn’t foresee all that and what it would mean for the country. And, as I said, many of them didn’t live long enough to address these issues.

But they were conscious of them, especially as they would affect the South after the war. That’s why someone like Thaddeus Stevens wanted to confiscate the planters’ land and redistribute it—redistribute the wealth—to those who had actually labored on it. Still, many old-time abolitionists, who had been around a long time, may have found it difficult to adopt a new outlook when conditions changed—and labor was no longer “free”.

Take someone like Higginson, who was lost for a time. He eventually pulled himself together toward the end of the century, but he didn’t really understand the problems represented by strikes and labor. Far from it. He only became outspoken again when the issue of Jim Crow became dominant in the 1890s. He certainly spoke out against the racism of, say, William Jennings Bryan. And he was a definite anti-imperialist.

DW: Not to beat around the bush, although I already have, one of the things that struck me about White Heat was its honesty, whether I agreed with every idea and assessment or not. You write about men and women without cant or jargon. …

BW: Frankly I have no idea. I don’t see the world that way. It’s an odd thing—when you sit down at the desk, especially after having written several books—the more experience you have, you realize that no matter what you do, somebody’s not going to approve of it, not approve of you. Writing then is a solitary and private act—and then you just say, damn it, I’m going to say what I think is true.

DW: The problem is, most people don’t operate that way.

BW: I can’t speak for them. I just have to be honest with myself. Because I feel that if I don’t say what I really think, and I’m criticized or it doesn’t work, then I’ll know it was my own fault. When I finish something, I feel that, well, perhaps this or that reader won’t like it, but I’ll stand by it. Perhaps in five years I won’t feel that way, I’ll decide I was wrong, but now I believe it. That’s how I manage to sleep at night.

And then there’s this: when I’m confronted, let’s say, by a poem of Dickinson’s, and I am overwhelmed, I think, what the hell, I may not understand it perfectly, does anyone entirely? Isn’t that in part what makes it great?—it speaks to so very many of us in a language that’s almost impossible to translate. That makes me feel better and allows me to go ahead and say what I get out of it.

Of course I enjoy what I do. To a certain extent, I feel free when I’m writing, or I try to feel free. In a social situation, you can’t always say what you think. But when it’s just you and the piece of paper, that’s different … and perhaps even more challenging.

Samuel Bamford, a reformer and weaver who led a contingent of several thousand marchers to Manchester from the town of Middleton, said he spent the evening of the massacre “brooding over a spirit of vengeance towards the authors of our humiliation.” Bamford told the judge at his trial for sedition that he would not recommend non-violent protest again.

Samuel Bamford, a reformer and weaver who led a contingent of several thousand marchers to Manchester from the town of Middleton, said he spent the evening of the massacre “brooding over a spirit of vengeance towards the authors of our humiliation.” Bamford told the judge at his trial for sedition that he would not recommend non-violent protest again.