In this video, Fernando Botero speaks about his Abu Ghraib art.

Today, to the exhibition of Colombian artist Fernando Botero in The Hague in The Netherlands.

Or, rather, two exhibitions close together.

One, of his drawings, mainly recent, from the 21st century in the Escher museum.

The other one, of fifteen big sculptures, mainly from the 1990s.

Together, they give a more balanced view of Botero’s work than individually.

Translated from an interview by Maja Landeweer with Botero, in Dutch daily Algemeen Dagblad, special Botero exhibition issue:

Botero started sculpture in 1975, when he had already been painting for 25 years.

“I had wanted to start earlier, but I could not do both at the same time.

Then, I stopped painting for a year, in order to learn sculpting.”

Meanwhile, Botero exhibits his sculptures and paintings on all continents, except for Australia.

In 1992, one of his paintings was sold for a million and a half dollars, the highest prize ever for a Latin American artist.

More on the Fernando Botero Abu Ghraib exhibition in The Hague, translated from Dutch press agency ANP:

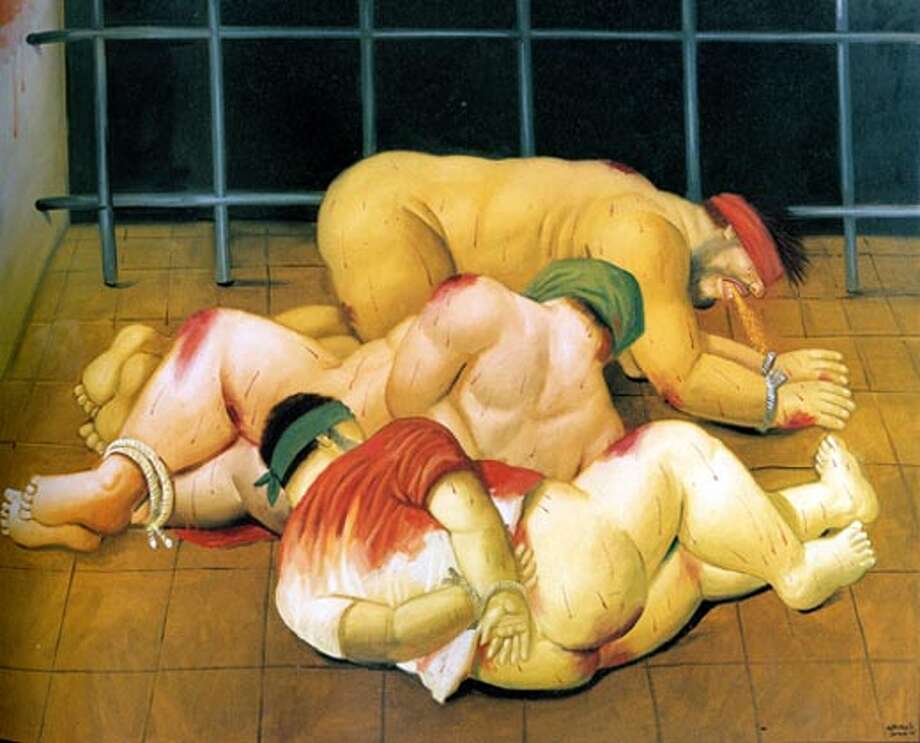

THE HAGUE – Ten [eleven, it turned out later] Abu Ghraib drawings by the world-famous artist Fernando Botero Angulo, briefly: Botero, are in museum Escher in the Royal Palace in The Hague this spring [and summer].

The photos and news items on the abuse in the Abu Ghraib prison also shocked Botero deeply, museum organizer John Sillevis says.

,,Ever since the first press publications, the Colombian is working on this.

This is a series on which he still continues to work; the images continuing to haunt throughout his head.”

Botero also in these drawings uses the round forms, characteristic for him, Sillevis says.

The drawings are not copies of the photographs which were such a painful surprise to the world.

However, according to Sillevis they are still immediately recognizable as inspired by them.

,,You see the humiliations, people with bags over their heads, nearly naked men with ladies’ underwear on.”

Sillevis says that Botero in those drawings basically carries on from his work inspired by unjust situations on his own continent, South America.

”However, Abu Ghraib really caused something to snap inside him.”

The drawings are part of a collection of fifty, which will be open to the public from 1 June up to 27 August.

There has always been a tendency of, more or less mild, criticism of society in Botero’s work.

Not surprising, seeing the influence of ‘subversive’ artists like Picasso, Goya, and Frida Kahlo on him.

The “fat” depictions of humans by Botero do not always say the same: sometimes, they stand for sensuality.

Sometimes, they ridicule ponderousness.

Like in the colourful drawing of an oversized man, fallen off his oversized horse.

In his Abu Ghraib paintings and drawings, they mean something else again: men, though strong and muscular, being grinded mercilessly by a state torture machine.

Botero’s courage in depicting Abu Ghraib should be praised, as he risked losing his more or less comfortable status as an “accepted” artist, whose mild criticism did not seem threatening enough to the establishment.

It resulted in vitriolic attacks on Botero by the far Right lunatic fringe, including columnist in Dutch daily Trouw Sylvain Ephimenco (from an “Algerie Francaise” “pied noir” colonial background).

Reactions like this are a sign that Botero hit the nail on the head.

The eleven Abu Ghraib drawings, being, unlike the paintings, in black and white, may be even starker than the paintings.

They, especially drawing “Abu Ghraib 37”, reminded at least one visitor of terrible torture which happened here in The Hague, very close to Botero’s exhibition now, over 300 years ago: in 1672, a monarchist mob tortured bourgeois republican politicians, the brothers Johan and Cornelis de Witt, to death in a horribly cruel way.

Somewhat like during the British Restoration, when republicans were tortured to death.

Botero’s non Abu Ghraib drawings are often related to his sculpture.

However, they also include still lives, often with bottles, maybe influenced by Pablo Picasso, or by Juan Gris.

And a drawing of a woman undressing (the suggested swift upward movement of her arms suggesting she is indeed undressing, not dressing).

The drawings are in the museum, dedicated to Dutch ‘op art’ graphic artist M. C. Escher.

In the 1930s, Escher was inspired by medieval Muslim architecture in Spain, like the mosque of Cordoba.

There is no big similarity between Botero and Escher, apart from that both started from reality to over-emphasize some aspects, subverting traditional ways of seeing.

Mathematics and Escher’s famous tesselations: here.

Sculptures

There are fifteen Botero sculptures in the open air exhibition on Lange Voorhout street.

Well, fourteen: the fifteenth, depicting a bishop, is in the nearby Monastery Church.

The first sculpture is Reclining woman.

Then, Motherhood.

Then, Dressed woman; somewhat ironically poking fun at a well dressed lady from well off social categories.

Maybe a bit in the vein of Goya, admired by Botero, who is said to have mocked the Spanish royal family in his portrait painting of them.

Then, Woman’s torso; left over from a complete statue about which the sculptor was not longer satisfied.

Then, a horse. Oversized, like not only his sculptures depicting humans, but also animals.

Then, a big human head.

Then, a sphinx.

Not in the Egyptian style (mainly depicting lion-male human, especially pharaoh, hybrids), but in the Egyptian influenced, but differently developed, Greek style: a winged lioness-woman hybrid.

The rear half of Botero’s sphinx is completely lioness, including lioness’ nails.

The front half is fashion conscious woman, including the carefully manicured longest fingernails of any woman or man in the exhibition.

Botero pays lots of attention to fingernails.

Then, a sculpture of a reclining woman eating an apple.

Then, a big sitting cat. Its posture puts it somewhere between statues of ancient Egyptian cat goddess Bast, and Garfield.

Then, two ballet dancers.

Then, a sculpture about the Greek mythology theme Leda and the swan.

White stripes on this sculpture marked that birds, seeing a bird depicted, also wanted to contribute.

Which birds?

I saw three species among the Botero sculptures: wood doves, domestic pigeons, and jackdaws.

Like the sculpture of the Rape of Europe, also in this Botero show, Leda and the swan reminds one of ancient Greek royal families who wanted to impress their subjects with supposed blood ties to the gods, especially supreme god Zeus.

That led to myths of Zeus, in various animal disguises, having sexual intercourse with mortal women.

Finally, unwittingly, these royal dynasty founding myths led to images of the Greek gods as sexually promiscuous, making them vulnerable to attacks from other religions like Christianity.

Next sculpture was Man standing on top of woman.

Finally, another reclining woman.

Brazilian M.C. Escher Exhibition is the World’s Most Popular Art Show? But how? Here.

Related articles

- Botero: ‘You Can’t Be Liked By Everybody’ (artnews.com)

- How much would Jesus weigh? (wnd.com)

- US contractor accused of Abu Ghraib human rights violations suing former prisoners (rinf.com)

- Abu Ghraib Torture Victims Sued by Their Torturers (commondreams.org)

- The barbarism of CACI et al versus Al Shimari (intrepidreport.com)

- Fernando Botero, “Reclining Priest”, 1977 (paintingsframe2000.wordpress.com)