By Owen Hatherley in Britain:

Socialists have often felt rather uncomfortable with Futurism.

This Italian art movement, founded in 1909, sang the praises of new technology, aeroplanes and the mass media – but it also exalted war and colonialism.

Many of its leaders, such as Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, later became outspoken supporters of fascism.

The Marxist critic Walter Benjamin attacked Futurism in the 1930s, contrasting it to the Russian Constructivist art movement that allied itself with the October 1917 revolution.

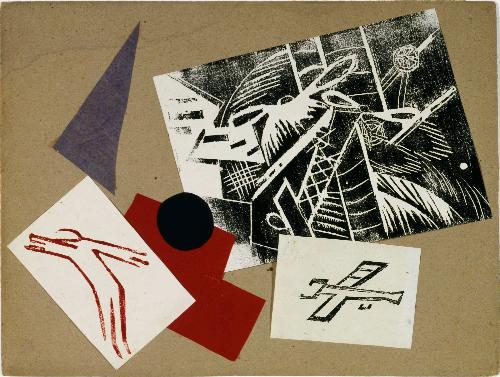

The paradox, however, is that Russian Constructivism grew out of Italian Futurism – as this timely exhibition at the Estorick Collection gallery in north London demonstrates.

A Russian group of Futurist artists was formed around 1910.

Their first manifesto, A Slap in the Face of Public Taste, appeared in 1912 and was composed by the poet and painter Vladimir Mayakovsky, among others.

The Russian Futurists had much in common with the Italians – they too romanticised technology.

But there were differences from the start.

Paintings and book illustrations by Kasimir Malevich and Natalia Goncharova show the influence of Russian folk art, particularly the “lubok”, or woodcut.

Against the realist pretensions of bourgeois art, the Russians saw the future in schematic, distorted figures drawn by anonymous peasant artists.

It’s also notable, considering Marinetti’s inclusion of “scorn for woman” in his Futurist Manifesto, that nearly half the Russian Futurists were female – Varvara Stepanova, Olga Rozanova, Lyubov Popova and Natalia Goncharova being the most prominent.

Promise

Another difference is the harsh, clear lines that creep into the Russian images from around 1913 onwards.

The “metallisation of the human body” promised by the Italian Futurists saw its fulfilment more in Malevich’s robotic figures than in the soft pastel blur of Italian painters such as Gino Severini.

Popova’s painting Portrait (1915), with the word “futurismo” emblazoned across it, shows the mid-point between the two styles.

The Futurist theme of a collision between man and machine took on a very different significance after 1914.

Marinetti’s Futurist group volunteered for the First World War.

Despite the death of their great sculptor Umberto Boccioni, they remained militaristic even after the war had ended.

The Russian response to the war was more ambiguous.

Initially Malevich and Mayakovsky (who had joined the Bolsheviks in 1908, but then drifted away from politics) designed propaganda posters with folksy representations of bayoneted Germans.

Their enthusiasm for war didn’t last long.

By 1915 Mayakovsky was roaring out anti-war poems like “You!”.

The war’s presence in Russian Futurist art also changed dramatically. Rozanova’s Universal War series used abstract shapes to create dehumanised depictions of the slaughter.

By 1915, Malevich had effaced human figures altogether and embraced abstraction. Meanwhile Vladimir Tatlin started using actual industrial materials in his exhibits.

Then came the Bolshevik revolution of 1917. Mayakovsky wrote at the time, “October. To accept or not to accept?

For me, as for the other Moscow Futurists, this question never arose. It is my revolution.”

See also here.

Jewish artists and the Russian revolution: here.

Radical Russia: Art, Culture and Revolution. How the Bolshevik Revolution saved avant-garde art: here.

Related articles

- Women’s Power: Sisters of the Revolution, Russia 1907-1934 @ The Groninger Museum (irenebrination.typepad.com)

- Century of Sound: 100 Years After Russolo’s “The Art of Noises” (createdigitalmusic.com)

Excellent post and linkage dearkitty 🙂

I felt Trotsky’s critique on futurism should be liked as well.

http://www.marxists.org/archive/trotsky/1924/lit_revo/ch04.htm

LikeLike

I’ve always felt that this was something like the difference between the progressive and revolutionary English Romantics and the reactionary and proto Fascist German Romantics.

REPLY by Administrator (I put it here, as my anti spam program absurdly refuses it as a comment):

Hi Jon, though the examples are about a century apart, I think this is an interesting comparison. Romanticism was a complicated movement with internal contradictions; see here.

I would not say the progressive-reactionary contradiction was exactly along national boundaries, however. Sometimes it even was across one individual: progressive English Wordsworth later became a reactionary, etc. And some German romantics (Beethoven, Hölderlin, Heinrich Heine) I would certainly not call “reactionary and proto Fascist.”

I do not know details of all Italian Futurist individuals, but maybe there was some opposition to the pro Fascist direction of their leaders.

LikeLike

Hi Lohan, thanks for your link!

By the way, links can be made clickable in Blogsome comments with HTML link code. If I edit a comment, it can be done with a menu.

LikeLike

I agree. I was oversimplifying for the sake of brevity. I was also drawing on Peter Viereck’s “The Roots of the Nazi Mind”. Viereck was not completely reliable. He seemed to have a personal dislike for Wagner. Still, I like the Russian constructivists and the English romantics, and see their art as somehow connected to my far left sympathies. Thanks as always for you interesting blog.

LikeLike

Thanks, Jon! More on Viereck here.

Futurism’s influence celebrated

Stella, Warhol, Hirst’s debt highlighted in Bergamo

(ANSA) – Bergamo, September 21 [2007]- The shock waves that crashed through the art world from Italy’s hugely influential Futurist movement are registered in a massive new show in this northern city.

The exhibit features 200 works by 120 artists including Futurism’s protagonists Giacomo Balla, Umberto Boccioni, Carlo Carra’, Gino Severini, Mario Sironi and Luigi Russolo.

An array of modern and contemporary artists influenced by Futurism’s iconoclastic energy includes America’s Frank Stella, Robert Rauschenberg, Andy Warhol and John Cage as well as Britain’s Damien Hirst and Gilbert and George.

The show has a vast cultural scope and extends into the world of literature, showing the influence of Futurist founder Filippo Tommaso Marinetti on tragic Russian poet Vladimir Mayakovsky. “The Futurists believed in the need to radically redesign the universe,” explained curators Giacinto Di Pietrantonio and Maria Cristina Rodeschini.

“This concept led them to perceive every form of artistic expression in a different way, including music, dance, photography, cinema, theatre and the design of living spaces and furniture.

“The show provides a rich sample of the vast body of art these ideas generated, linking the works to other areas of the worlds of culture and industry”.

The first section, entitled Futurism Revisited, juxtaposes paintings by Futurist big guns with works by artists influenced by them over 50 years later.

Visitors can admire Balla’s stylish Numeri Innamorati (Numbers in Love, 1920), Boccioni’s intriguing painting of a woman in a hat, Modern Idol (1911), alongside Hirst’s Beautiful, Chaotic, Psychotic, Madman’s, Crazy, Psychopathic, Schizoid, Murder Painting (1995).

Another highlight is photography-painting duo Gilbert and George’s 2004 work Pull, which depicts the smartly dressed artists with their fingers in each other’s mouths on a bright red background.

The second section, Metropolitan Energy, concentrates on the output of Futurist architects and designers.

There is Antonio Sant’Elia’s 1914 plan for a combined train station-airport and Fortunato Depero’s avant-garde vision of Skyscrapers and Tunnels.

Among the modern architects shown is the acclaimed Massimiliano Fuksas.

Another part of the show is called Anarchy and Tradition.

It looks at some of the eyebrow-raising art that followed Futurism, with works by Italian concept artist Piero Manzoni – famed for his cans containing the ‘Artist’s Shit’ – and French Surrealist-Dadaist Marcel Duchamp.

A section called The Entertainment Society includes paintings by American contemporary artists Andy Warhol and Keith Haring.

The Bergamo exhibit is one of many initiatives being organized in Italy in the run-up to the 100th anniversary of Futurism’s birth in 2009.

Futurism was officially launched with the publication of a manifesto by Marinetti in French daily Le Figaro on February 20, 1909.

The manifesto expressed the Futurists’ key ideas – a love of technology, industry and speed, and a loathing of the past.

Futurism’s rampant colours and violent energy extolled the merits of a new, technologically advanced age.

The show, entitled Il Futuro del Futurismo (The Future of Futurism), runs at Bergamo’s Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art (GAMeC) from September 21 to February 24.

LikeLike

008-07-01 12:26

Russia celebrates Futurism

Moscow kicks off Italian movement’s centenary celebrations

(ANSA) – Moscow, July 1 – Moscow is the first non-Italian city to pay its respects to Futurism as Italy’s influential 20th-century art movement approaches its 100th birthday. The Pushkin Museum is hosting a lavish exhibition of 200 works commemorating the impact of Italian Futurists and their Russian counterparts on modern art.

”The exhibit offers a wide selection of works illustrating the main manifestos of Futurism, as well as looking at how these ides were implemented in practical terms,” explained one of the show’s coordinators, Gabriela Belli of the Trento and Rovereto Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art (MART).

”It showcases works ranging from Umberto Boccioni’s radical innovations in the field of sculpture – including his exceptional 1913 piece, Unique Forms of Continuity in Space – through to the theoretical reflections of Antonio Sant’Elia, who envisioned a style of architecture based on ‘the new beauty of cement and steel”’. Other artists featured in the exhibit, which will spotlight all of Futurism’s best-known stars, include Giacomo Balla, Carlo Carra’, Gino Severini, Fortunato Depero and Enrico Prampolini among others. According to art critic Giacinto Di Pietrantonio, ”the Futurists believed in the need to radically redesign the universe”.

”This concept led them to perceive every form of artistic expression in a different way, including music, dance, photography, cinema, theatre and the design of living spaces and furniture”.

The bulk of the show will focus on Italian work but a final section organized by the Pushkin Museum alone will dip into Russian Futurism and its relationship with the Italian scene. Belli described the ties between the two groups as ”extremely close”. ”The two countries shared a cultural closeness in developing a radically revolutionary artistic movement that, unlike Cubism, also had an impact on the social and cultural life of the era, proposing art as a form of freedom and progress”. Among the featured Russian artists are Natalia Goncharova, Mikhail Larianov, Liubov Popova and Alexandra Exter.

The exhibit offers a foretaste of a number of events planned over coming months, starting with a major show at the Pompidou in Paris this October. The show will then move on to Rome’s Quirinale in February and the Tate in London.

Elsewhere, the MART is hosting its own Futurist show in January. Milan will explore the subject with two exhibits in February and October, while Futurist works will be spotlighted by the Correr in Venice next June. Futurism was officially launched with the publication of a manifesto by Marinetti in French daily Le Figaro on February 20, 1909.

The manifesto expressed the Futurists’ key ideas – a love of technology, industry and speed, and a loathing of the past.

Futurism’s rampant colours and violent energy extolled the merits of a new, technologically advanced age.

Art historians have long recognised the part played by Futurism in shaking up the sleepy art world of the turn of the century, according them an honoured place between the Impressionists and the Cubists.

LikeLike

Women and the Russian Revolution: `Our task is to make politics

available to every working woman’

By Lisa Macdonald

The following is the Introduction to On the Emancipation of Women, a

collection of the key articles and speeches on women’s liberation by

Russian revolutionary V.I. Lenin, published by Resistance Books. On the

Emancipation of Women is available online at

http://www.resistancebooks.com

http://www.resistancebooks.com/catalog/product_info.php?cPath=29&products_id=89

LikeLike

Pingback: Soviet art and architecture, London exhibition | Dear Kitty. Some blog

Pingback: Theo van Doesburg, Nelly van Doesburg, dadaism, De Stijl | Dear Kitty. Some blog

Pingback: Soviet artist Alexander Rodchenko exhibition in London | Dear Kitty. Some blog

Pingback: Italian divisionist painters and politics, 1891-1910 | Dear Kitty. Some blog

Pingback: New World War I book | Dear Kitty. Some blog

Pingback: French symbolist art exhibition in the Netherlands | Dear Kitty. Some blog

Pingback: Resistance and art, from the 1871 Paris Commune to today’s Iraq war. Part I | Dear Kitty. Some blog

Pingback: Russian painting, 100 years ago | Dear Kitty. Some blog

Pingback: Futurism and politics | Dear Kitty. Some blog

Pingback: Kasimir Malevich in Amsterdam | Dear Kitty. Some blog

Pingback: Resistance and art, from the 1871 Paris Commune to today’s Iraq war. Part II | Dear Kitty. Some blog

Pingback: Art, social movements and history, exhibition | Dear Kitty. Some blog

Pingback: Art and the 1917 Russian revolution | Dear Kitty. Some blog

Pingback: Italian futurism, exhibition in New York City | Dear Kitty. Some blog

Pingback: Painter Kasimir Malevich, 1879-1935 | Dear Kitty. Some blog

Pingback: Opposition in Germany against World War I | Dear Kitty. Some blog

Pingback: British artists and World War I, exhibition | Dear Kitty. Some blog

Pingback: War and art 2014-now, exhibition in England | Dear Kitty. Some blog

Pingback: Theo van Doesburg, Nelly van Doesburg, dadaism, De Stijl | Dear Kitty. Some blog

Pingback: Paul Nash, painting against World War I | Dear Kitty. Some blog

Pingback: United States artist Georgia O’Keeffe exhibition in Canada | Dear Kitty. Some blog

Pingback: Jewish Soviet author Ilya Ehrenburg | Dear Kitty. Some blog

Pingback: Soviet poet Vladimir Mayakovsky | Dear Kitty. Some blog

Pingback: Poet Mayakovsky in theatre play | Dear Kitty. Some blog

Pingback: Painter Raphael on film, review | Dear Kitty. Some blog

Pingback: British artist Gustav Metzger interviewed | Dear Kitty. Some blog

Pingback: Bauhaus architecture, 1919-2019 | Dear Kitty. Some blog

Pingback: Ritratto, premiere of opera on Luisa Casati | Dear Kitty. Some blog