This video from South Korea says about itself:

From the ashes of war, German artist Kathe Kollwitz uncovers humanity

18 March 2015

Works by a famous German artist who is known for her emotionally powerful artwork are on display here in Seoul.

Our Yim Yoonhee joins us with more about this very moving exhibition.

Käthe Kollwitz created strong images that touched millions of lives around the world for their depictions of people struggling with the poverty and devastation in the aftermath of war.

This is a rare opportunity to see these works.

Have a look.

A mother, desperate to feed and fend for her children in a country ravaged by war.

The image is one of over 50 original works by the 20th century German painter, printmaker and sculptor Käthe Kollwitz that are being shown at the Seoul Museum of Art.

But inside these charcoal sketches, inside the shadows, are hungry children, traumatized mothers,… the victims of poverty and World War I,… people that artist Kollwitz just couldn′t ignore.

“After the war, the remaining families had a very hard time. There was no relief in sight, no counseling and no one to defend them. This artist chose to bring attention to them.”

The exhibition is divided into two parts one dedicted to the squalid lives of members of the working class prior to 1914, while the latter part shows works that illustrate the living hell experienced by people in Germany in the aftermath of World War I.

Kollwitz was a well-recognized and respected artist in the art community, but she went beyond being an artist and contributed to humanity, bringing awareness to those left in the shadows of this world.What was the artist′s relationship to the war?

Kollwitz was married to a doctor who often tended to the poor, and that greatly affected her career.

In terms of the war, she lost her youngest son to World War I, which you can imagine had a great influence on her works.

Many of her works have names such as “Grieving Parent”, “The Widow” and “The Sacrifice”, so it′s clear that art really became her outlet.

And what legacy does the artist leave behind, other than her works?

There are over 40 German schools named after the artist, but many books, movies and even modern dance pieces have featured characters inspired by Kollwitz.

There are also many statues, some made by Kollwitz herself and some created after her works that are housed at many locations throughout Germany… to commemorate the war and especially its victims.

The artist really brought much-needed attention to all of the unseen suffering during wartime.

By Jenny Farrell in Britain:

An artist of peace and the people

Saturday 7th October 2017

Jenny Farrell pays tribute to the great German artist and sculptor KÄTHE KOLLWITZ

Käthe Kollwitz’s work reflects the events of the first half of the 20th century yet she continues to stand tall among anti-war artists and champions of the dispossessed of the present time.

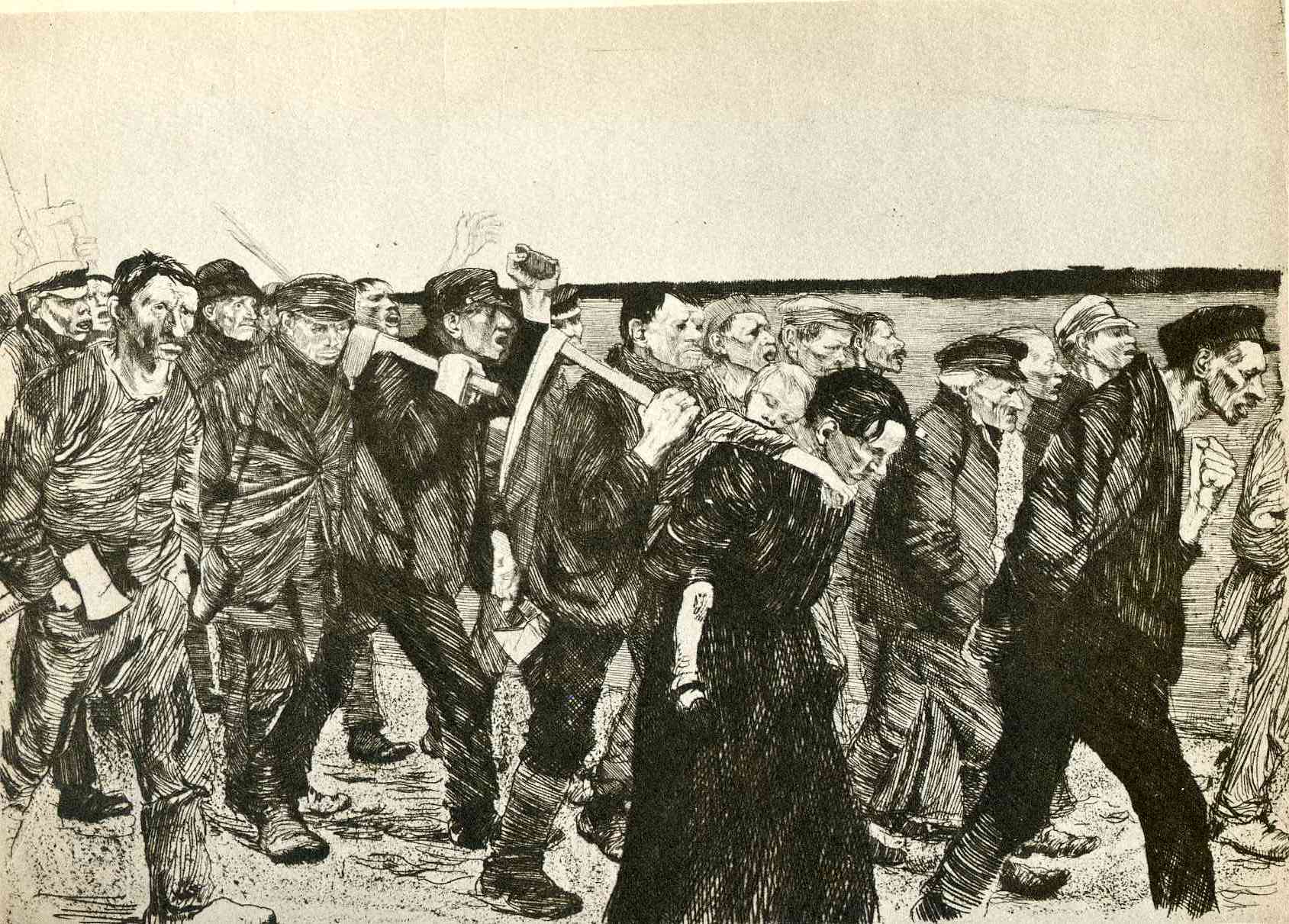

Kollwitz broke completely with bourgeois aesthetics and made the subjugated and humiliated working class her sole artistic subject. Her work eloquently expresses the force, resistance and humanity of this class. Very often, she focuses on individuals or small groups who exemplify the fate of thousands, balancing their misery with dignity and human kindness.

This year marks the 150th year since her birth in Kaliningrad. The daughter of a bricklayer who recognised his daughter’s artistic talent early on, she was barred from studying art as a woman in her hometown and moved to Berlin and Munich to pursue her education.

There, she met radical artists of her time and married the socialist Karl Kollwitz, a medical doctor who lived among, and treated, the poor of Berlin. Together they dwelled in the then impoverished working-class — now gentrified — Prenzlauerberg district for most of their lives. Here, she gave birth to two sons and created her substantial oeuvre.

Kollwitz’s breakthrough work, which defined her artistic signature, was the cycle The Weavers, inspired by witnessing in 1894 the premiere of Gerhart Hauptmann’s drama of the same name about the uprising of Silesian weavers a half century before.

Over and above connecting present misery with that of the past, Kollwitz focused on resistance against social injustice. Reflecting on this early experience, she noted in her autobiography that the play, research and work on the weavers’ rising was a key event in her artistic development.

The cycle consists of three lithographs — Poverty, Death, and Conspiracy — and three etchings — March of the Weavers, Riot, and The End — with The March of the Weavers becoming Kollwitz’s best-known work.

Stirred by her working-class surroundings and involvement, Kollwitz’s second cycle The Peasant War, going back to the German uprising of the 1520s, also centres on the rebellion of the exploited and suppressed against social injustice.

Peasant War is worked in a variety of techniques — etchings, aquatint and soft ground and the cycle is counted among Kollwitz’s greatest achievements.

In one of the images, After the Battle, a mother searches through the dead at night, looking for her son; and the sense of loss and grieving became a central theme in Kollwitz’s work after the death of her son Peter in the early days of WWI.

From then on, mothers protecting their children, fighting for their survival and grieving their death became an ever-present motif in Kollwitz’s work. She conveys a profound sense of unspeakable tragedy and of human responsibility to fight against death-spawning militarism and war. The people, the victims, are also those where humanity is found and the only source of resistance.

In 1919, Kollwitz began work on the woodcut cycle War, responding to the tragedies of WWI. Seven images reflect her unspeakable pain. Stark, large-format woodcuts feature the anguish of war. In The Sacrifice, a mother sacrifices her infant, while in The Volunteers Kollwitz depicts her son Peter beside Death, who leads a group of young men to war in a frenzied procession.

Once again eliminating specific references to time or place, Kollwitz created a universal condemnation of such slaughter.

The January 1919 assassination of Karl Liebknecht — sole German parliamentarian to vote against further war loans in the summer of 1914 — by right-wing militias, occasioned her famous woodcut In Memoriam Karl Liebknecht. It is a moving tribute to this communist leader, mourned by the people he represented, who pay their final respects in a shocked, yet gentle fashion.

In 1924, Kollwitz created her three most famous posters, Germany’s Children Starving, Bread and Never Again War. After the nazi rise to power, in the mid-1930s, Kollwitz completed Death, her last great cycle of eight lithographs.

More heartbreak was wrought on her in 1942, when her grandson Peter fell victim to Hitler’s war. This death came after that of her husband Karl, who had died of illness in 1940.

Kollwitz died just a few days before WWII ended, on April 22, 1945. She has left us with unforgettable images of the horrific events and epic struggles of her lifetime. Her images remain profound indictments of a system that perpetuates such social injustice and crimes against humanity.

The free exhibition Portrait of the Artist: Käthe Kollwitz runs at the Ikon Gallery in Birmingham until November 26, details: here.

Berlijn, 25 oktober 1916

Opnieuw vind ik alles uitzichtloos. Waarom toch? Niet alleen bij ons gaat de jeugd vrijwillig en welgemoed de oorlog in, ook in andere landen gebeurt het. Mensen die onder andere omstandigheden goede vrienden zouden zijn, gaan elkaar te lijf.

Heeft de jeugd dan geen kritische zin? Geeft ze altijd gehoor aan een oproep? Zonder na te denken? Slikt ze domweg alles wat haar wordt verteld? Is deze oorlog wat jongeren willen? De waanzin: jongeren in Europa zijn elkaar wederzijds aan het afslachten.

Nooit zal ik dit kunnen begrijpen. Ik weet alleen dat onze jongens – net als onze Peter – twee jaar geleden gehoorzaam ten strijde trokken en dat ze bereid waren te sterven voor Duitsland. Ze stierven – vrijwel allemaal. Ze stierven in Duitsland en ze stierven bij de vijand, bij miljoenen.

Toen de predikant de vrijwilligers zegende, sprak hij van de Romeinse jongeling die in de afgrond sprong en hem daarmee sloot. Dat was één jongen. Alle jongens weten nu dat ze zijn voorbeeld moeten volgen. De uitkomst is echter geheel anders. De afgrond heeft zich niet gesloten. Miljoenen levens heeft hij al verslonden en de diepte blijft onverminderd gapen.

En Europa, heel Europa, blijft zijn beste en kostbaarste bezit offeren, als in het oude Rome – terwijl er niemand is die het offer waard is.

Käthe Kollwitz (1867-1945), Duits beeldend kunstenaar; haar zoon Peter sneuvelde op 17-jarige leeftijd in 1914. Ingekort fragment uit Die Tagebücher. Akademie Verlag, 1989.

LikeLike

Pingback: German art students protest against neo-fascism | Dear Kitty. Some blog

Pingback: German painter Emil Nolde and nazism | Dear Kitty. Some blog

Pingback: The German Die Brücke painters and Hitler | Dear Kitty. Some blog

Pingback: German pro-peace artist Kollwitz and the USA | Dear Kitty. Some blog

Pingback: Pro-peace artist Käthe Kollwitz, Los Angeles exhibition | Dear Kitty. Some blog

Pingback: German anti-war artist Käthe Kollwitz exhibition | Dear Kitty. Some blog