This 12 November 2019 video, the trailer of the film My Rembrandt, says about itself:

What makes Rembrandt’s paintings technically so extraordinary, and why are different people so deeply affected by his oeuvre, or a specific work? Centuries after his death, his paintings are still a source of drama and gripping plot twists.

Rembrandt’s paintings have lost none of their appeal in the 350 years since his death. Collectors worldwide cherish the magic of the Dutch master’s work.

This entertaining documentary shows the passion of a variety of Rembrandt enthusiasts. An eccentric, aristocratic Scot is looking for the ultimate place to hang his beloved portrait of a woman reading, and an animated Amsterdam art dealer has his eye out for a second chance to discover a “new” Rembrandt—this descendant of an old merchant family, whose ancestor was once painted by Rembrandt himself, has got something to prove.

An ambitious American businessman and his wife proudly make “their” Rembrandts available to the Louvre, and the Rothschild family’s decision to put Rembrandt’s wedding portraits of Marten Soolmans and Oopjen Coppit on the market threatens to provoke a diplomatic row between the Netherlands and France.

On 26 January 2020, we went to see this film by Oeke Hoogendijk. Earlier, I had seen another film by Ms Hoogendijk, about the reconstruction of the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam.

My Rembrandt, more than being about Rembrandt himself, is a film about what happens around his paintings in the 21st century. It raises questions between the relationship between art and money; between art and social classes in history.

These issues have at least two sides. On the one hand, about Rembrandt himself and money and social classes. On the other hand, about Rembrandt’s works, money and social classes in our 21st century. It turns out that lots of money in art may destroy friendships between people and governments.

Rembrandt was luckier financially than Vincent van Gogh and many other artists. Van Gogh sold just one painting for little money while he was alive. However, after his death, Van Gogh, in a cruel twist of economical mechanisms, like quite some others, became an artist off whom some people made very much money. Rembrandt sold many paintings, usually for good money. But, as he spent much on eg, attributes for his paintings, he went bankrupt and died relatively poor. After his death, like with many other artists, some people who had never contributed a drop of paint to his art got very rich off it.

As for Rembrandt and social class: like Rubens, Rembrandt lived in the time of the Low Countries’ revolt against the kings of Spain. The Spanish monarchs managed to defeat that uprising in the south, in what, roughly, is now Belgium. However, the north became the independent Dutch republic. Rembrandt lived in the bourgeois Dutch republic. Rubens in the Spanish Netherlands, ruled by princes and nobles. The differences in social context between Rembrandt and Rubens meant differences in the subjects of their art.

In the Dutch Republic, there was no monarchical court comparable to most 17th century European countries.

There was only the Stadhouder‘s court.

Which would have liked very much to be a princely court like elsewhere in Europe; but constitutionally wasn’t.

Rembrandt got a commission from that princely court (princely, as the Stadhouders were also absolute monarchs in the tiny statelet of Orange in southern France).

But when his portrait of Princess Amalia von Solms, wife of Stadhouder Frederik Hendrik, turned out to be not flattering enough, his relationship to that court deteriorated.

A Hermitage Amsterdam exhibition noted that Stadhouder Frederik Hendrik prefered painters from the feudal southern Netherlands, though that region was the military enemy, to “bourgeois” northern painters like Rembrandt. He also prefered Gerard van Honthorst to Rembrandt as a painter of portraits of his wife. Honthorst was not from the Spanish occupied southern Netherlands. However, his home province Utrecht in the central Netherlands was less bourgeois rebellious than Rembrandt’s Holland. And Honthorst had spent much time in feudal Italy.

So, Rembrandt got most of his commissions for painting not from the Stadhouder’s court, but from bourgeois merchants, especially in Amsterdam city: the ruling class of the newly independent republic. They were as rich, or often richer, as nobles in other countries. Usually, they did not live in castles in the countryside, but in houses along canals like the Amsterdam Herengracht.

In one of the first scenes, the Rijksmuseum says they would like very much to have a painting which is now not in any of the houses to which Rembrandt sold his work, but in a big feudal castle in Scotland.

This Rembrandt work, Old woman reading, is owned by the Duke of Buccleuch. If for some reason, the castle owners would no longer want it, then the Rijksmuseum would like very much to bring it back to the city where it was painted.

A Rembrandt painting which is already in Amsterdam is this portrait of the merchant and mayor Jan Six.

The Six family still owns it. In the 19th century, this originally bourgeois dynasty got the title of nobility jonkheer (baronet).

Another family who got a title of nobility then was the Rothschild family, originally bankers. In the first part of the film, Baron Éric de Rothschild was still the owner of the Rembrandt’s wedding portraits of Marten Soolmans and Oopjen Coppit.

However, it seems that the Rothschild family is not as rich and powerful as some conspiracy theorists think, not as good in tax dodging as some other rich persons: Baron Éric de Rothschild’s brother owed debts to tax authorities. To pay these, Éric de Rothschild needed 160 million euros. The proceeds of selling his beloved portraits of Marten Soolmans and Oopjen Coppit, hanging at both sides of his bed in Paris.

Éric de Rothschild does not like interviews, and the filmmaker had just one hour for talking to him. Previously, an appointment for an interview had turned out to be impossible because of a Yellow Vest demonstration in Paris.

Ms Hoogendijk also made Marten & Oopjen, a TV film about the wedding portraits of Marten Soolmans and Oopjen Coppit.

So, these portraits cost 160 million euros. The Paris Louvre museum did not have that money. Neither had the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam. But the Rijksmuseum collected money and was almost at 160 million. Then, the French government banned these two paintings from going from private property in France to public property in the Netherlands. A diplomatic conflict between the European Union member governments of France and the Netherlands was imminent. It turned out to be not as sharp a conflict as the proxy oil war between the European Union member governments of France and Italy in Libya. The Dutch government, being smaller than the French one, gave in. There was a compromise: both museums paid 80 million euros, mostly government money. And the two paintings would sometimes be together in the Louvre, sometimes together in the Rijksmuseum.

A major role in this documentary is Jan Six. Not the 17th-century Jan Six depicted by Rembrandt, but a 21st-century relative. An art historian and art dealer, that Jan Six, ‘Jan Six XI‘, used to work at Sotheby’s. He claims to have discovered two unknown works by Rembrandt. No Rembrandt painting had been rediscovered for 42 years.

This is the first one: the biblical scene about Jesus saying Let the little children come to me.

Some unknown 17th century painter had painted over the Rembrandt original, so recognizing the work as a Rembrandt was not obvious. It is probably from when Rembrandt was still young and lived in Leiden.

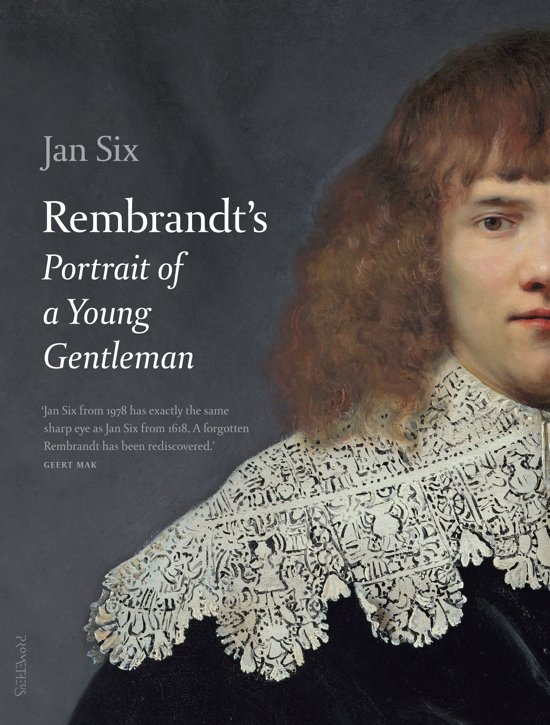

This is the other newly discovered Rembrandt: Portrait of a Young Gentleman.

Jan Six wrote this book about it.

The discovery showed how money in art can ruin friendships. Jan Six had bought the painting for 160,000 euros on behalf of an anonymous investor from an owner who did not suspect it was a Rembrandt. Fellow art dealer Sander Bijl claimed that Six had broken an agreement to buy the painting together. The purchase also caused a conflict between Six and Rembrandt expert Ernst van de Wetering.

Van de Wetering says in the film: ‘The conflict is about money. I hate talking about money. These paintings belong to all of us!‘

An interesting remark on the problems of art in a world of capitalism.

Pingback: Painter Jan Steen during coronavirus crisis | Dear Kitty. Some blog

Pingback: Vincent Ehindero Blogger Award, thank you thebibliophilewriter! | Dear Kitty. Some blog