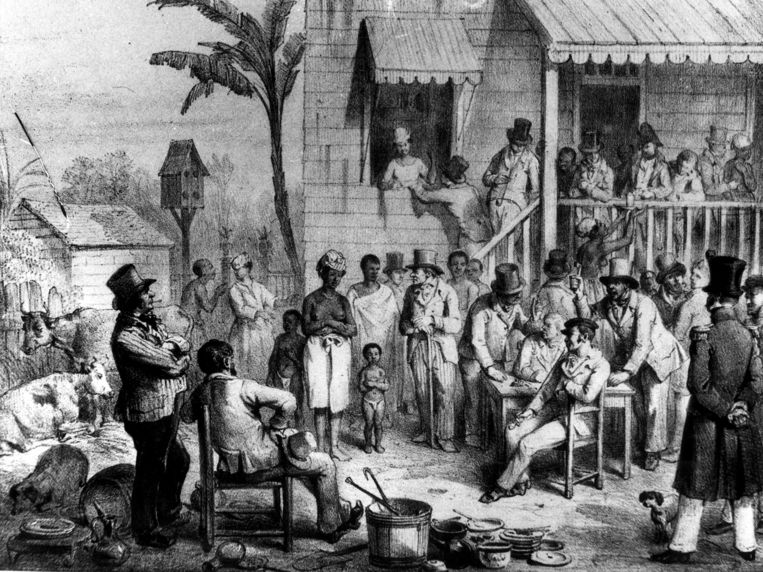

This picture is about slave trade in the Dutch colony Suriname in 1839, public auction of a slave woman and her two children.

Translated from Dutch daily De Volkskrant, 25 June 2019, by Geertje Dekkers:

Economic weight of slavery much larger than imagined; “Earnings in 1770 roughly comparable to the port of Rotterdam now”

Slavery yielded the province of Holland

the economically most important part of the pre-1795 Dutch republic

at its pinnacle about 10 percent of GDP, and the whole of the Netherlands 5 percent, historians have calculated. From shipbuilders to notaries and coffee sellers: they all benefited from the trade in people and their work on plantations.

In 1770, Holland people earned more than 10 percent of their gross national product from the slave trade and slave labor. Tobacco traders, sugar refineries, shipbuilders, money lenders and others got that income from the transport of enslaved people from Africa to America [not even taking into account Dutch slavery in South Africa and Asia], and from the work they did there on plantations. In the Republic of the Netherlands as a whole, the financial interest was half that that year: just over 5 percent. Economic historians Pepijn Brandon and Ulbe Bosma of the International Institute of Social History calculated this for an article in the journal TSEG to be published on Wednesday.

The article should help solve a tough question: to what extent was Dutch wealth based on exploitation? Earlier generations of historians pointed out in their answers that the slave trade itself was not very lucrative: it represented about half a percent of all national income. But slaves yielded more than just their selling price. In the surveyed year 1770 they worked together 120 thousand man-years on the land for the Dutch market. Eg, they produced coffee, tobacco and sugar, which was mainly processed in the Holland region: in late 18th-century Amsterdam people found ‛in streets and even in alleys, even more so in cellars, sugar refineries”, says contemporary Jan Hendrik Reisig. In the whole of Holland there were around 150 in 1770. …

Shipbuilders and merchants

And then there were the notaries who laid down agreements, the money lenders and shipbuilders who made the trade possible, the merchants who resold goods, and so on. Together they earned the aforementioned 10 percent of Dutch GDP based on slavery, the article said.

But was that percentage, and the 5 percent in the rest of the Netherlands, big or small? A comparison with now sheds some light on the matter. The Dutch 10 percent was comparable to the share of health care in today’s national GDP. And the 5 per cent of the entire Republic the authors themselves compare with the port of Rotterdam, and all related services and logistics. They make up 6.2 percent of the current Dutch economy. A percentage point more than slavery in 1770.

According to the authors, the percentages mean that the economic weight of slavery was much greater than previously thought, and of vital importance to the Netherlands: “Slavery kept the economy going in one of the most developed commercial societies,” they state in a text for the press.

A quarter of the economy of Vlissingen city in Dutch Zeeland province was slave trade.

about all you need to know about the high “civilization” of Europe in these days is they increased their money 10 fold and their food supply doubled when slavery started up full steam.

I only found that out in 4th year of college … explained the whole art history thing (master paintings much more light weight to ship than gold).

LikeLike

5 juli, Amsterdam: bijeenkomst over het grote profijt van slavernij en kolonialisme voor de Nederlandse economie

Op 5 juli organiseert Pakhuis de Zwijger in Amsterdam de bijeenkomst “Slavernij en de Nederlandse economie”. Met als sprekers onder anderen Pepijn Brandon, Ulbe Bosma, Marjolein van Pagee en Mano Delea. Moderator is Jurenne D. Hooi. Vrijdag 5 juli. Vanaf 20:00 uur. Pakhuis de Zwijger, Piet Heinkade 179, Amsterdam. Lees meer:

https://www.doorbraak.eu/5-juli-amsterdam-bijeenkomst-over-het-grote-profijt-van-slavernij-en-kolonialisme-voor-de-nederlandse-economie/

LikeLike

Pingback: Amsterdam streets named after anti-slavery, anti-colonialism fighters | Dear Kitty. Some blog

https://www.staff.universiteitleiden.nl/news/2019/07/the-impact-of-the-slave-trade-on-dutch-economy

LikeLike