This Italian video is about Giuseppe Pellizza da Volpedo, Italian divisionist painter (1868-1907).

From British daily The Morning Star:

A living torrent

(Monday 23 June 2008)

EXHIBITION: Radical Light: Italy’s Divisionist Painters 1891-1910

CHRISTINE LINDEY looks at a style of painting that caused shock waves throughout the Italian establishment at the end of the 19th century.

Fascinated by the analysis of colour and optics by scientists Chevreul and Rood, the French artist Seurat applied their theories to painting in the 1880s.

Small dots of colour juxtaposed onto a white surface would mix in the eye of the viewer when seen from a certain distance, so retaining the luminosity of natural or artificial light.

Differences of tone to convey the solidity of objects were created by adding dots of complementary colour. For example, yellow and red dots merge into orange, while adding blue dots created a darker orange without darkening the overall tonality of the painting. He called this method “divisionism,” but critics derided it as “pointillism” and the name stuck in France.

These ideas soon spread. They were brought to Italy by the dealer-critic-painter Grubicy. There, divisionists tended to prefer using threads or dashes of divided colour rather than dots. Never an organised movement, the Italian divisionists’ concerns lay within the opposing ideologies of socialism and mysticism.

The political situation in 1890s Italy was highly charged as the growth of the electoral franchise, literacy and industrialisation raised class consciousness. Challenging rural poverty and exploitation, the recently formed labour movement called for land redistribution and higher wages.

Those peasants who escaped the countryside to find building and domestic work in the fast-growing cities, notably Milan, found themselves poorly housed and underpaid. The ensuing well-supported strikes and demonstrations were broken up with fierce police and army brutality.

Socialist artists including Pellizza, Nomellini and Balla equated divisionism‘s scientific, rational basis with a modernism which matched their political beliefs. Their paintings would be radical in form and subject.

When working on the Living Torrent (1895-6), Pellizza wrote: “I am attempting a social painting … a crowd of people, workers of the soil, who are intelligent, strong, robust, united, advance like a torrent, overwhelming every obstacle in its path, thirsty for justice.”

A massive painting, its life-size peasants march resolutely towards the viewer, the central figure suffused with light in a powerful representation of the might of organised political struggle.

Longoni‘s The Orator of the Strike (1890-1) depicts an impassioned mason speaking high above the rally from a builder’s scaffolding. In the background, the army charges fleeing protesters with fixed bayonets.

Longini was at this outlawed May Day protest in Milan in 1890. The exhibition at which the painting was first shown opened on the following May Day, when another protest, also outlawed, took place.

The left-wing press reproduced and discussed such works, spreading their power beyond the walls of art museums and galleries. Some argued that they were over-didactic, others defended them as effective calls to arms.

Such fiercely topical works were seen as a threat by the authorities. Longini was put under police surveillance. So harsh was state repression that he and Pellizza later retreated into a vague symbolism.

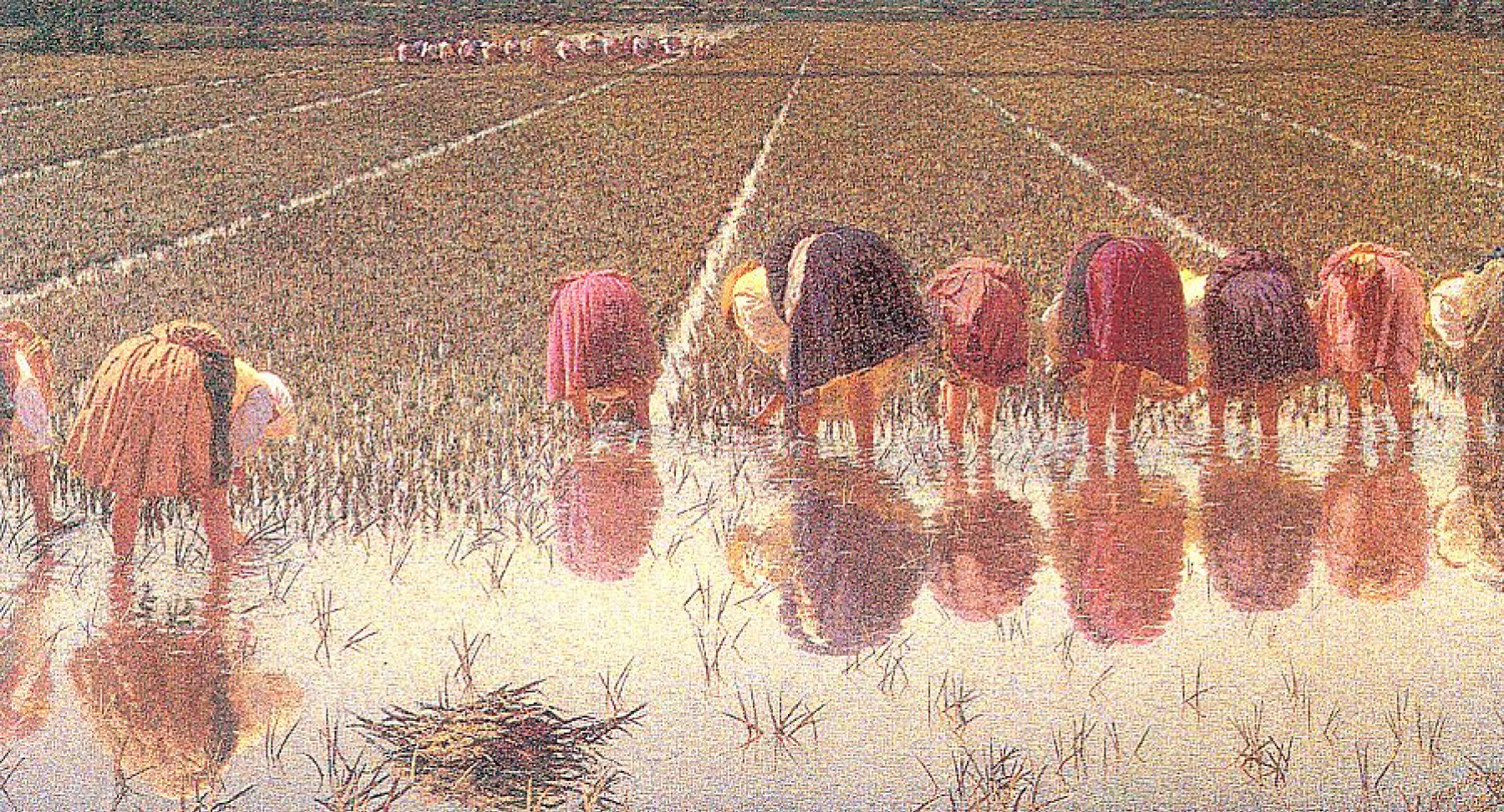

Other divisionists exposed social injustice. Morbelli‘s For Eighty Cents! (1893-5) shows a line of peasant women ankle-deep in the foetid water and stinking heat of rice fields. The title scoffs at their derisory pay. …

For the symbolists, divisionism was a means of conveying states of mind rather than a positivist engagement with realism. Previati’s and Segantini’s quasi-mystical paeans to the sanctity of motherhood belong to a conservative Catholic tradition which resisted political and social change.

Segantini’s well-fed, tranquil peasants are far removed from Pellizza’s angry, hungry living torrent. Portraying peasant life as reassuringly idyllic and unchanging, his works conveyed a conservative ideal.

Grubicy’s idealised landscapes, influenced by Japanese prints, represent the city dweller’s rose-coloured longing for nature unsullied by human habitation or intervention.

Divisionism was the first aesthetically radical manner to be widely known in Italy. Within a culturally provincial climate, its adoption symbolised the rejection of tradition in favour of modernity. As some divisionists were also socialists, aesthetic radicalism became associated with political radicalism in the public mind and the manner became doubly synonymous with all that was outrageous.

This has masked the fact that, by the 1890s, appreciating and collecting esoteric avant garde art signified sophistication and social superiority for a section of the haute bourgeoisie. …

However, the following generation of Italian divisionists boldly capitalised on the legacy of the pioneers. Balla’s, Boccioni’s and Carra’s paintings exploded into an uncompromising riot of modernist colour and expressive brush marks so genuinely radical that they had an international impact. They soon aligned themselves with Marinetti’s futurists which inherited and perpetuated the twinned antagonistic ideological roots of Italian divisionism.

This exhibition gives a clear account of these divergent tendencies and influences. It is a pleasure to see the socialist works of Balla, Nomellini, Pellizza and Longini. Arguably the most stunning room is the last one, in which we can see icons of modernism such as Boccioni‘s The City Rises (1910) and Balla’s spectacular Street Light (1910-11).

However, be prepared for the many works which were anything but radical too.

Exhibition shows until September 7 and costs £8 or £4 on Tuesday afternoons and Wednesdays 6-9 pm. Concessions £7-£4.

See also here.

Related articles

- ‘Matisse: In Search of True Painting’ at the Metropolitan Museum of Art (galleristny.com)

- Doing a Henri Matisse in three new paintings (creativepotager.wordpress.com)

- Cubist Painter Flats – The Nicholas Kirkwood ‘Picasso’ Slipper is a Humble Work of Art (TrendHunter.com) (trendhunter.com)

- How Leonardo da Vinci’s angels pointed the way to the future (guardian.co.uk)

- Peter Schjeldahl: “Inventing Abstraction, 1910-1925,” at MOMA. (newyorker.com)

- Today’s Birthday: ROSA BONHEUR (1822) a painter (euzicasa.wordpress.com)

- Today’s Birthday: FERDINAND HODLER (1853) a Painter (euzicasa.wordpress.com)

- Murillo and Justino de Neve: The Art of Friendship, Dulwich Picture Gallery (standard.co.uk)

2008-07-03 12:20

Divisionists arrive in London

National Gallery show includes works by Boccioni and Balla

(ANSA) – London, July 3 – Divisionism, the 19th-century art movement that gave birth to Futurism, is the focus of a new exhibition in the National Gallery in London.

‘Radical Light – Italy’s Divisionist Painters’ features around 80 paintings, bringing the work of the Divisionists to the UK, where it is still little known. The movement had a short life, running from 1891 until 1910, when it split into Symbolism and Futurism, but included artists who would later gain international renown, such as Giacomo Balla and Umberto Boccioni.

The Divisionists were mainly active in Italy’s industrial heart, Milan, and were strongly influenced by the scientific and technological progress of the time. This fascination with technology resulted in their most characteristic technique: the use of pure, unmixed threads of colour, which imbued their work with an intense luminosity. They were also known for their commitment to Socialist ideals, leading many to focus on the harsher side of life: the poor, labourers, factory workers and field hands.

The Orator of the Strike (1890-91) by Emilio Longoni is one such piece, while another is Giuseppe Pellizza da Volpedo’s famous The Fourth Estate (1895), which shows a mass of workers ”marching” towards the viewer.

Boccioni’s The City Rises (1910) follows the same revolutionary theme but is entirely different in conception, depicting a swirling mass of vivid colour. However, there are also a number of works on display that seem to share little common ground outside the painting technique, producing vastly different canvases on an array of subject matters. Some show daily life, others quiet landscapes, while a few tackle supernatural or moral themes. A number of works highlight the rural path taken by Plinio Nomellini, Pellizza and Vittore Grubicy de Dragon, such as the latter’s striking dawn piece, Morning (1897). Other painters, such as Gaetano Previati focused on symbolism, while Angelo Morbelli’s series of elderly subjects, painted between 1902 and 1903, examine a darker side of everyday life. The launch of Futurism in 1909, with the publication of the movement’s manifesto, lured many Divisionists onto a new path, which is explored at the end of the exhibition. The show includes Balla’s 1911 masterpiece, Streetlight, which contrasts the brilliant luminescence of an electric lamp with the pale glow of the moon.

These crossover works may be more accessible to visitors but the exhibit shows how most had their roots firmly planted in Divisionism. The exhibit runs in the National Gallery until September 7, after which it travels to Zurich, Switzerland.

LikeLike

2008-10-20 16:05

Neo- impressionists arrive in Milan

More than 100 works on display at Palazzo Reale

(ANSA) – Milan, October 20 – Milan is hosting Italy’s first ever exhibition on the Neo-Impressionists, whose exploration of pure colour produced a series of brilliant paintings at the end of the 19th century. The show in Palazzo Reale features key works by the main figures of the movement, which flourished from the mid-1880s until 1910. Around 100 works are on display, starting with the earliest paintings by Georges Seurat and Paul Signac, who were the driving force behind the movement.

The Neo-Impressionists had their roots in Impressionism but shifted their focus away from the latter’s fascination with light towards line and colour.

Like Italy’s Divisionist movement, the Neo-Impressionists invented a technique that used tiny dots of pure colour to create an image that could only be perceived by standing back from the work. Signac famously compared the ethos to the music produced by an orchestra: ”In order to listen to a symphony, you don’t sit in the middle of the orchestra, but in the position where the sounds from the various instruments mingle, creating the harmony desired by the composer,” he wrote. ”Similarly, faced by a ‘divided’ painting, it is best to first stand at a sufficient distance in order to absorb the whole, before moving closer to study the chromatic effects up close”. Seurat and Signac first exhibited works in this new style at an 1884 exhibition in Paris but the term Neo-Impressionism was only coined by an art critic three years later. Rather than painting outdoors and capturing the sense of a moment in time as the Impressionist did, the Neo-Impressionists generally worked indoors and produced slow, thoughtful and careful pieces.

The movement attracted most followers in France and Belgium, reflected in the balance of work on display, with paintings by Albert Dubois-Pillet, Henry van de Velde, Willy Finch, Johannes Theodorus Toorop, Theo van Rysselberghe’ George Morren, Maximilian Luce, Constantin Meunier, Georges Lenunen and Louis Hayet, among others.

However, there are also works by Italian artists Giacomo Balla, Luigi Russolo and Gaetano Previati, who were part of the parallel Divisionist movement that flourished in the years before Futurism.

The exhibition runs in Milan until January 25.

LikeLike

Nuoro fetes early 20th-century Italian art

Balla, Boccioni and Medardo Rossi among artists featured in show

02 March, 13:48

Nuoro fetes early 20th-century Italian art (ANSA) – Rome, March 2 – A selection of masterpieces by the greatest stars of early 20th-century Italian art is opening in the Sardinian town of Nuoro shortly. The exhibition at the Nuoro Museum of Art, opening on March 5, will showcase over 60 works on loan from top institutes around the country. The ten artists featured are among those credited with ushering in some of the greatest developments in Italian art during the first three decades of the last century. The exhibition unfolds through a series of rooms, with the work of individual artists grouped together. It starts with three beautiful wax sculptures by Medardo Rosso, which are offset with a selection of early Divisionist works by Giacomo Balla, Umberto Boccioni and Gino Severini before their discovery of Futurism.

The exhibition follows through with rooms devoted to the some of the most famous works by Severini and Balla, as well as several paintings by Carlo Carra’.

This carries the show into the 1920s, where they discovered Futurism, a movement that was fully embraced by Balla but eventually dropped by Severini and Carra’, who shifted back to a more classical style. Also from this period are a number of paintings by Mario Sironi, including some 1925 masterpieces and a series of early preparatory sketches, which laid the groundwork for later large-scale works.

The next stage will focus on the output of Surrealist artist Giorgio De Chirico, founder of the metaphysical art movement. Several of De Chirico’s best-known works have been loaned for the event, intended to offer a brief overview of his artistic development. Paintings by De Chirico’s brother, Alberto Savinio, also have their own section. The large-scale mythological works explore his fascination with the concepts of philosophy and narrative in art. The exhibition wraps up with a tribute to Giorgio Morandi, best known for his muted paintings and detailed drawings.

Several of his stunning still lifes and two landscape paintings have been selected for the show. Capolavori del ‘900 italiano. Dall’Avanguardia al Ritorno all’ordine (20th-Century Italian Masterpieces. From The Avant-Garde To The Return To Order) runs in Nuoro’s Museum of Art from March 5 until June 6.

LikeLike

Pingback: Futurism and politics | Dear Kitty. Some blog

Pingback: Kasimir Malevich in Amsterdam | Dear Kitty. Some blog

Pingback: Art, social movements and history, exhibition | Dear Kitty. Some blog

Pingback: Italian futurism, exhibition in New York City | Dear Kitty. Some blog

Pingback: New Hercules Segers paintings discovered | Dear Kitty. Some blog

Pingback: Painter Leonardo da Vinci, new film, review | Dear Kitty. Some blog

Pingback: Caravaggio exhibition in London | Dear Kitty. Some blog